Because of my trip home in December, my research grant period was extended by just a couple of weeks. As such, February 28th didn’t mark the final day of my grant, as was originally scheduled.

In hindsight, this is probably a good thing, as February ended with a flurry of research activity for me. This is largely because February 28th, 1947 was the beginning of a series of protests that ultimately led the KMT-led government to kill tens of thousands of Taiwanese citizens, and contributed to the KMT’s decision to impose martial law on the island after 1949.

Though the so-called 2/28 Incident 二二八事件 is one of the most infamous and formative dates in the history of modern Taiwan, discussion of the event was long suppressed during Taiwan’s era of martial law. In fact, according to the Taipei Times, the 228 Incident was only mentioned four times in Taiwan’s major newspapers between 1948 and 1984.

In the years since Taiwan’s transition to full democracy, however, 228 has gradually gained more and more prominence as a site of remembrance and reflection, as well as a chance to celebrate the progress that Taiwan has made socially and politically over the past few decades.

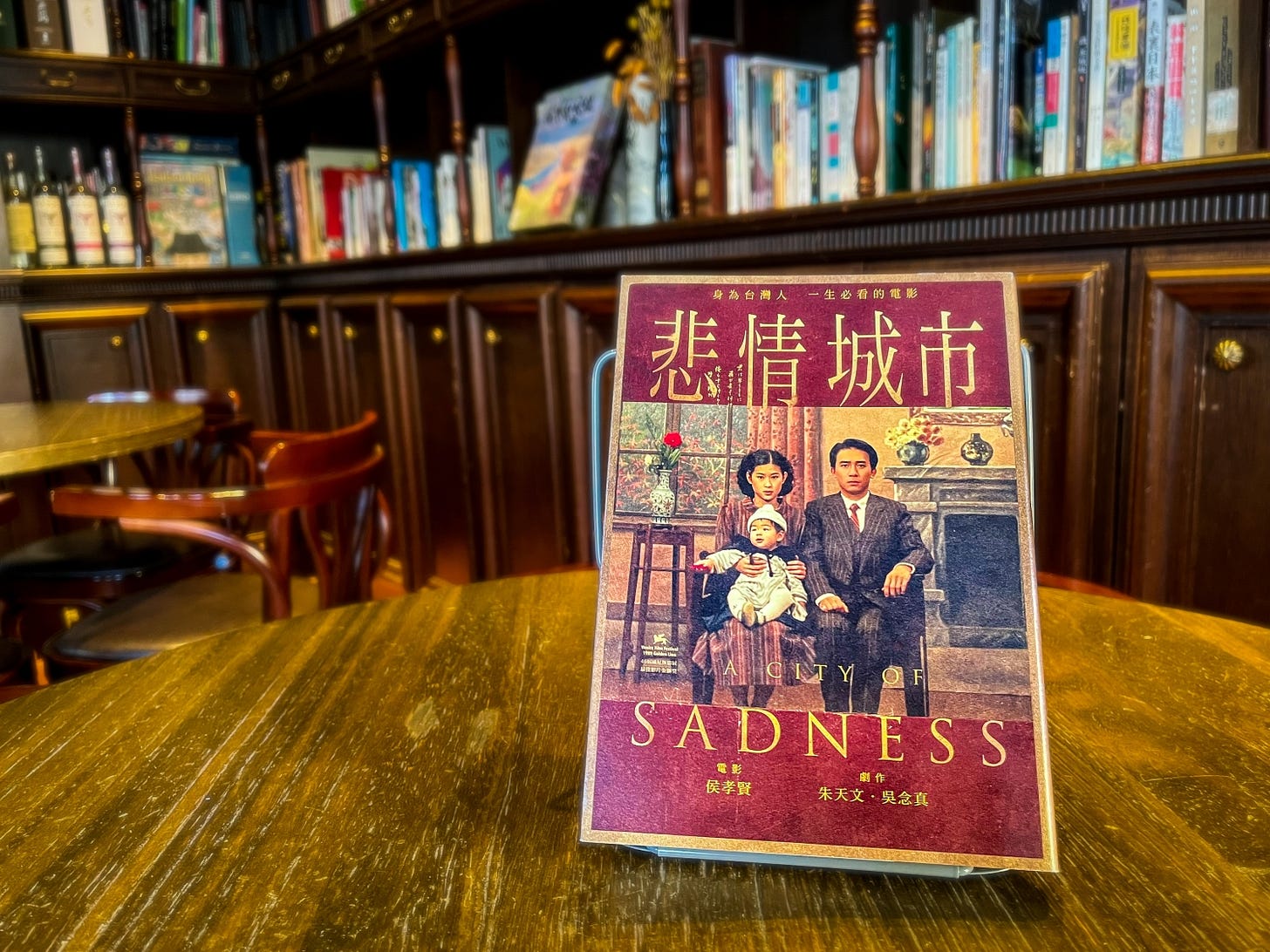

But February 28th is also a huge topic. On the one hand, it has inspired books, plays, and films, including seminal works such as Hou Hsiao-hsien’s City of Sadness 悲情城市, the icon of Taiwanese film that launched the socially aware New Taiwanese Cinema movement to international acclaim, and more recent offerings such as Untold Herstory 流麻溝十五號.

The aftermath of the 228 Incident is equally well-worn territory for documentarians, covered in recent films such as Yeh Shih-Tao: A Taiwan Man 台灣男子葉石濤 (which I have talked about before), and only slightly-less-recent documentaries like The Taste of Wild Tomato 野番茄 (which I talk about in today’s post).

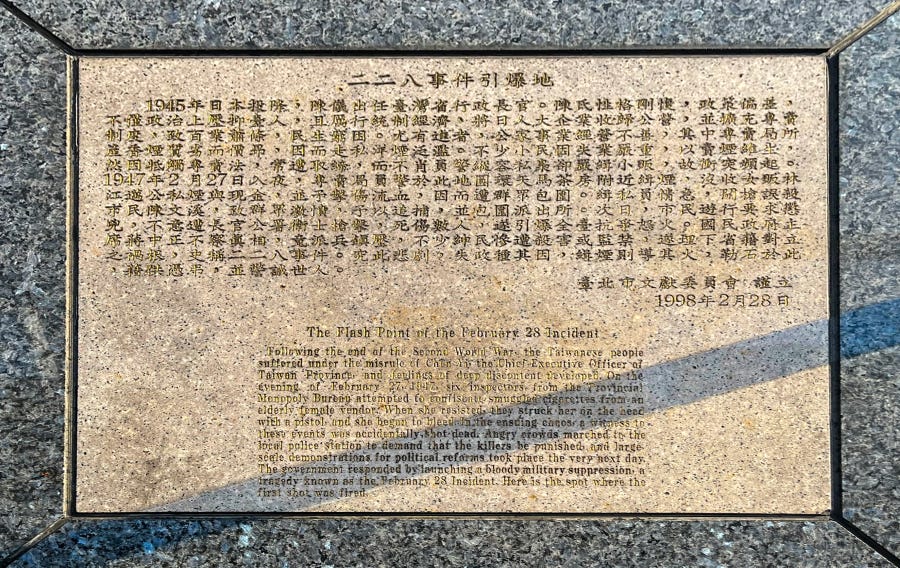

228 is also the subject of entire museums, parks, and memorials. Taipei alone hosts a raft of memorializations and educational institutions, including the 228 Peace Memorial Park 二二八和平公園, national museums such as the National 228 Memorial Museum 二二八國家紀念館, city museums such as the Taipei 228 Memorial Museum 台北二二八紀念館, and private museums such as the Nylon Cheng Liberty Foundation and Memorial Museum 鄭南榕紀念館.

But 228 also remains a sensitive, painful topic. It remains politically divisive, largely along party lines. And it remains a matter of urgency for activists who fear a gradual weakening of public awareness and emotional investment in this event that has so shaped the modern Taiwanese experience.

As you may have gathered already, today’s post is not exactly a toe-tapper. Also, because of the quantity of materials I collected over the weekend, it is a monstrously long post.

Nevertheless, I’m going to crack on with it, as writing this provides me an opportunity to organize some of the materials that I collected over a weekend of national remembrance, education, and activism. These materials encompass public lectures, film (re-)screenings, large-scale music festivals, and talks by key federal legislators.

Critically, the topics these events touch on are not simply matters of settled history. Rather, they touch on the very nature of how contemporary Taiwan constructs its history, its present, and its future. In short, 228 remembrances and recollections remain at the heart of debates over what it means to be Taiwanese today.

I know that I have brought up the 228 Incident and the White Terror in this blog before. But in this case, rather than just linking to Wikipedia, I think it’s important to provide some historical detail first. This will both help you understand why this is such a central debate in contemporary Taiwanese political life, and set the stage for what follows in the latter portion of this article, when I actually describe the events I attended.

A Brief History of the 228 Incident

In 1945, Japan officially relinquished control of Taiwan, along with most of their imperial holdings, ending 50 years of Japanese rule in Taiwan. At this time, the Kuomintang 國民黨 took control of the island, just as the civil war between China’s Republican and Communist parties started heating up again.

What followed was a period of significant instability in Taiwan. The newly appointed governor of the province, Chen Yi 陳儀, stacked the government with his lackeys, who turned the riches of Japan’s former colonial holding into their personal piggy bank. Historian Hsiao-ting Lin states that a combination of corruption, mismanagement, and civil war stressors in Mainland China resulted in widespread food shortages, up to 50% of UN-provided reconstruction aid vanishing, and staggering unemployment and inflation: “During the year 1946, it was estimated that 80 percent of the native-born Taiwanese industrial workers lost their jobs, and by January 1947 local commodity price indices had risen 700 percent for food, 1,400 percent for fuel and building materials, and 25,000 percent for fertilizer.”1

In so many cases, mass protest and unrest are triggered not by large symbols of inequity, but by banal examples of state cruelty and political ineptitude. The protests triggered by George Floyd’s murder started with a suspected counterfeit $20-dollar bill. Interdepartmental wrangling about who was at fault for the fatalities in an apartment fire in Ürümqi contributed to the White Paper Protests 白纸抗议, China’s largest protests since Tian’anmen. The Berlin Wall was brought down by a bureaucratic error (albeit one broadcast on national television).

In the case of 228, it was a cigarette that broke the camel’s back. Struggling to make ends meet in the face of draconian state monopolies and hyperinflation, a 40-year-old widow was selling contraband cigarettes on the evening of February 27th, 1947 at the Pegasus Teahouse 天馬茶房, located on the outskirts of Taipei’s Dadaocheng 大稻埕 district (somehow, I always end up back in Dadaocheng). Military police confiscated the cigarettes, and hit the widow over the head with the butt of a rifle. A group of men came to the woman’s assistance, the police fired shots, and at least one onlooker was killed.

The next day, February 28th, a group of protestors marched to Chen Yi’s headquarters seeking restitution. Instead, they received a salvo of machine-gun fire from security forces armed with military-grade weaponry.

In the subsequent weeks, as protests reached a scale that threatened to topple the provincial government, Chen Yi pretended to negotiate with a committee made up mainly of Taiwanese intellectuals. In reality, he had already cabled Nanjing asking for military reinforcements. When the reinforcements landed in northern Taiwan, they went on a rampage that often specifically targeted members of the Taiwanese intelligentsia, particularly those involved in the Settlement Committee.

The situation deteriorated from there, with casualties mounting rapidly. Numbers range wildly in terms of the number of people killed—some NGOs estimate the number to be as 100,000, while some politicians have suggested that “only” 800 people were killed.2 Nevertheless, media and scholars alike both in Taiwan and abroad generally estimate that between 18,000 and 28,000 Taiwanese were killed in the uprising and subsequent military crackdown, a figure that tallies with the 1992 report produced by the KMT-controlled Executive Yuan.

Unfortunately, the story gets worse before it gets better. You see, much of the official blame for the 228 Incident has sought to avoid implicating Chiang Kai-shek, with responsibility placed solely on Chen Yi. In 1995, this narrative received a significant blow when a Chen Yi’s former body guard reported to the the Executive Yuan that he had handed Chen Yi a cable from Chiang Kai-shek saying, “Kill them all, keep it secret.”3 Though this cable has never been found, Hsiao-tang Lin’s investigation of Chiang Kai-shek’s diaries has shown that the Generalissimo personally endorsed the use of military force against the protestors.4

Lin’s work also shows that, despite public arguments claiming an age-old link with Taiwan, Chiang essentially regarded the Taiwanese as suspiciously “foreign.”5 Two years later, when the KMT fled to Taiwan, this lack of trust toward the Taiwanese would lead Chiang to functionally lock islanders out of governance through a mix of linguistic suppression (the local Chinese language of Taiyu was banned along with Japanese, meaning that Taiwanese intellectuals were linguistically “unfit” to serve in a Mandarin-speaking government), legalistic sleight of hand (the KMT government represented all of China, so obviously people who had never left the island of Taiwan couldn’t expect to represent the Mainland), and banning of opposition parties.

Finally, following the 1949 rout of China’s Nationalist Party, the 228 Incident provided the excuse for the KMT government impose martial law on the island, a situation that continued for 38 years—the longest continuous period of martial law in history, according to some speakers in this past weekend’s memorial events.6 And it led to the extended period of intensive state surveillance known as the White Terror, in which the state imposed strict limits on association, publication, and speech, and during which further tens of thousands of people were arrested, executed, or simply disappeared. During the entire period of the White Terror, discussion of the 228 Incident was a no-go zone.

Martial law was not lifted in Taiwan until 1987.

Commemoration in 4KHD

For anyone who has been reading for a while, you might remember that, during my trip to Jiufen 九份, I made a fairly big deal out of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s City of Sadness (Beiqing chengshi 悲情城市).

Released just two years after the end of martial law, it was the first film to explore the 228 Incident. It was also the first Taiwanese work to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. Thus, it was not only the first film to blow the lid off of the silences surrounding Taiwan’s traumatic history, it was also one of the films responsible for bringing the artistic movement of Taiwanese New Cinema to global attention. As such, it seems eminently appropriate both that this film receive the 4K treatment that so many other films have in recent years.

It’s also no surprise that the film’s re-release should coincide with the beginning of the 228 long weekend this year. I went and saw this film on the day of its re-release, Friday, 24 February, in the state-of-the-art theater at the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute, the institution that spearheaded the film’s restoration.

There’s a lot that could be said about this movie. Indeed, entire books have been written about it (and about the portrayal of trauma in Taiwanese film and literature.)7 When I put it in the context of the other events I attended this weekend however, I am particularly struck the way it handles the gamut of emotions and experiences shaped by the 228 Incident and the White Terror.

To begin, City of Sadness is not a total hatchet job of the early KMT era. In fact, it captures the ray of hope that glimmered briefly in Taiwanese intellectual circles after the announcement of Taiwan’s cession to Republican China, a moment reflected in one of the film’s few musical moments, when a group of young intellectuals offers a boisterous (and occasionally in-tune) rendition of “Along the Songhua River” 松花江上 (heard in the video below in a modern performance from Mainland China). This song comes from the Chinese War of Resistance against Japan and includes lyrics such as, “When will I be able to return to my homeland?”

Following the arrival of the KMT government, the film touches on many of the same themes addressed in scholarly writing. Grumbling around dinner tables tackles discontent with Taiwan’s rising prices, and the corruption of Chen Yi and his lackeys. The government’s rapidly changing language policies shows up in a scene in the local infirmary in which all of the doctors and nurses, suddenly legally mandated to abandon Japanese and Taiyu at work, drill Mandarin phrases such as, “Where does it hurt?”

More important than what gets said, however, is what the film leaves unsaid. City of Sadness is set in and around Jiufen, and therefore the events of the film do not directly show the attack on civilians as it unfolded in Taipei. But as news of trouble trickles out from the capital over the radio, we know that the film’s protagonist Wenqing and his close friend, the young intellectual Hiroe (note his Japanese name), go to Taipei to take part in “something important.” Upon their return, it seems that both are fleeing, though it is not immediately clear from what.

Ultimately, Hiroe leaves home, never to return again. Later, we watch as Nationalist troops find the mountain hideout of Hiroe, where he and his compatriots are summarily shot. The scene is strangely quiet, with the muffled yells of soldiers and protestors mingling with the sound of mountain grasses rustling in the wind. Only the sharp, but still distant-sounding, report of rifles and the dull thud of bodies confirms aurally what the viewer’s eyes see.

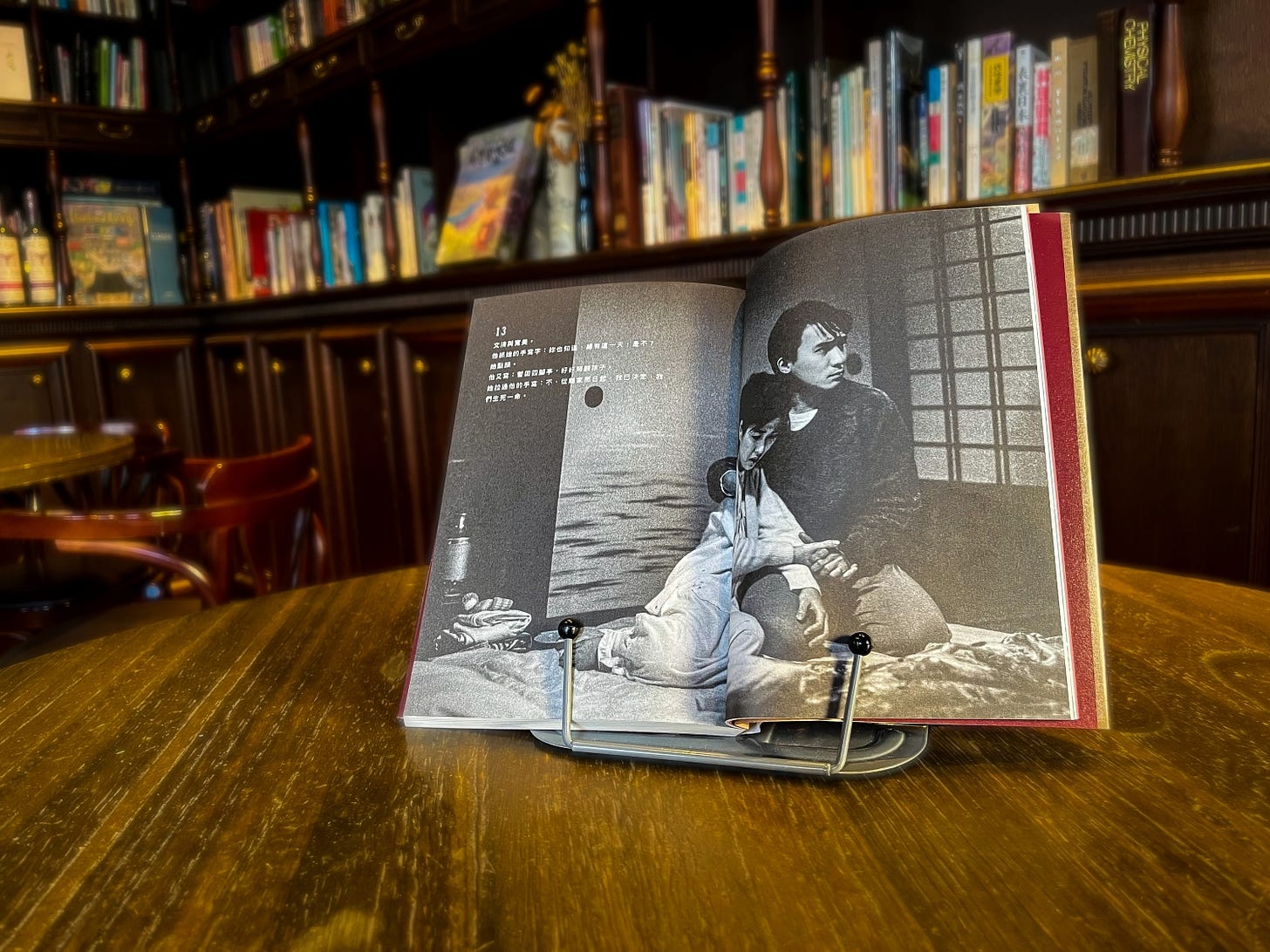

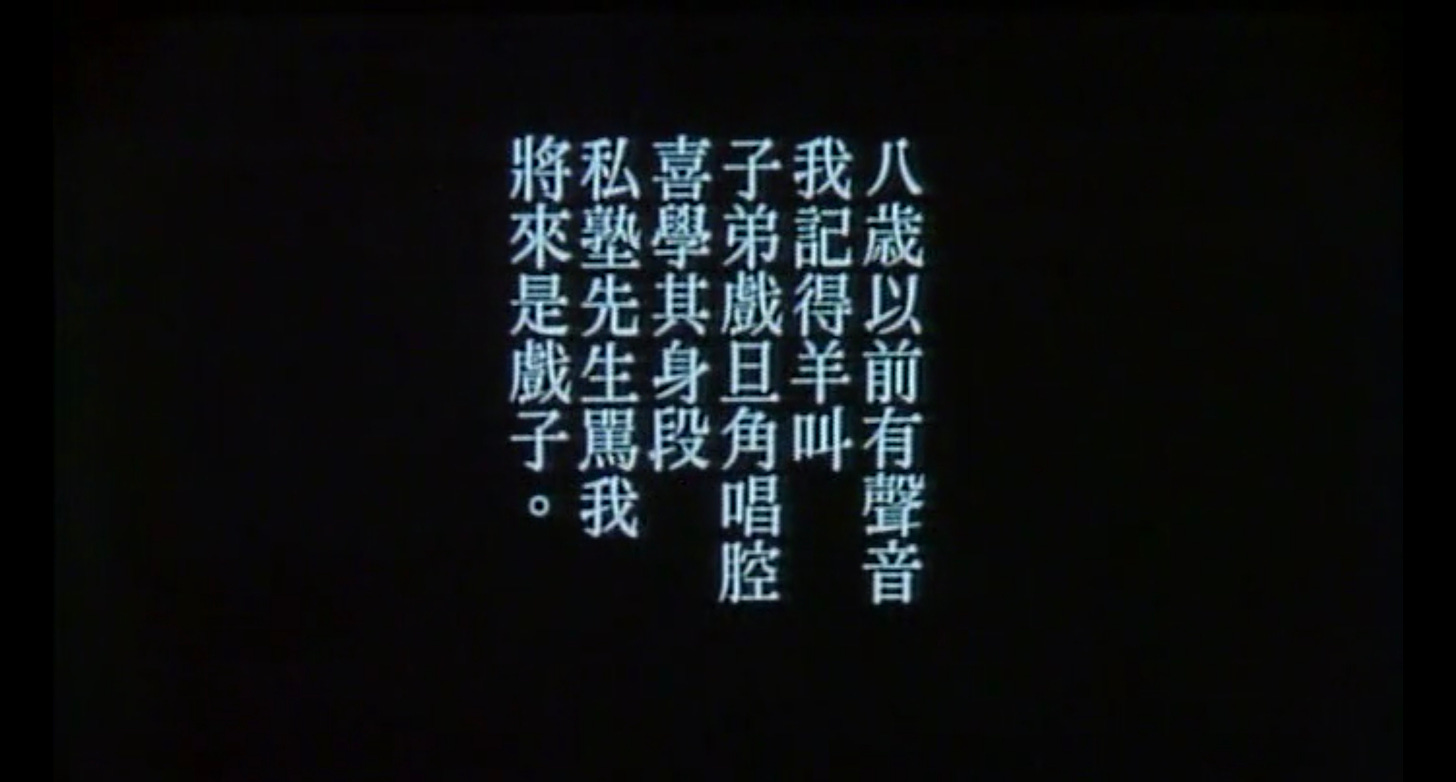

At its heart, though, City of Sadness deals with silence more literally. As a result of a childhood head injury, Hiroe’s best friend, the gentle photographer protagonist Lin Wenqing 林文青 (played by Tony Leung 梁朝偉 at his most devastatingly debonair) is mute, communicating with friends and loved ones through pads of paper that are hung on nails and pegs in every room of the house. Wenqing’s interactions with his world are selectively revealed to viewers through stark intertitles, in which white characters are superimposed on a black background, the photographic negatives of his communications with friends and loved ones.

In the main, we are not asked to feel sorry for Wenqing. His is a life of rich friendships, loving family, and fulfilling work through which he has gained his community’s respect. But late in the film, he argues with his best friend, Hiroe: after their flight from Taipei, Wenqing wants to join Hiroe’s cause in the mountains; Hiroe wants Wenqing to return to Jiufen and marry his sister Hiromi 吳寬美, who has for years loved Wenqing. In the midst of their frantically scribbled argument, the inability to rapidly articulate his thoughts breaks through, and Wenqing is reduced to pounding the rickety table on which the two men are writing.8 Even for one accustomed to it, the weight of an unbreakable silence, foisted upon Wenqing by a fateful moment of ill luck, can at times become too much to bear.

The film ends with a report from Hiromi, now wife to Wenqing, and mother of their child, writing to a family member. “[Wenqing] has been arrested. We still don’t know where he is. Once we had planned on escaping, but there is no way to escape … I have searched and inquired everywhere in Taipei, but I have no news.” Hiromi’s letter ends with some mundane remarks about her child’s growth, and the camera cuts to a long shot of the family eating. No one mentions Wenqing, as the silence that for decades surrounded the 228 Incident settles over Wenqing’s family.

Months ago, I suggested that the wave of 4K restorations of Taiwanese cinema (and Asian cinema more broadly) represents a process of canonization, in which sponsoring companies and institutes like Criterion and the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute define the works that define the nation. I think that the 4K restoration of City of Sadness fits well within this narrative. It is, after all, widely regarded as one of the defining pieces of Taiwanese cinema.

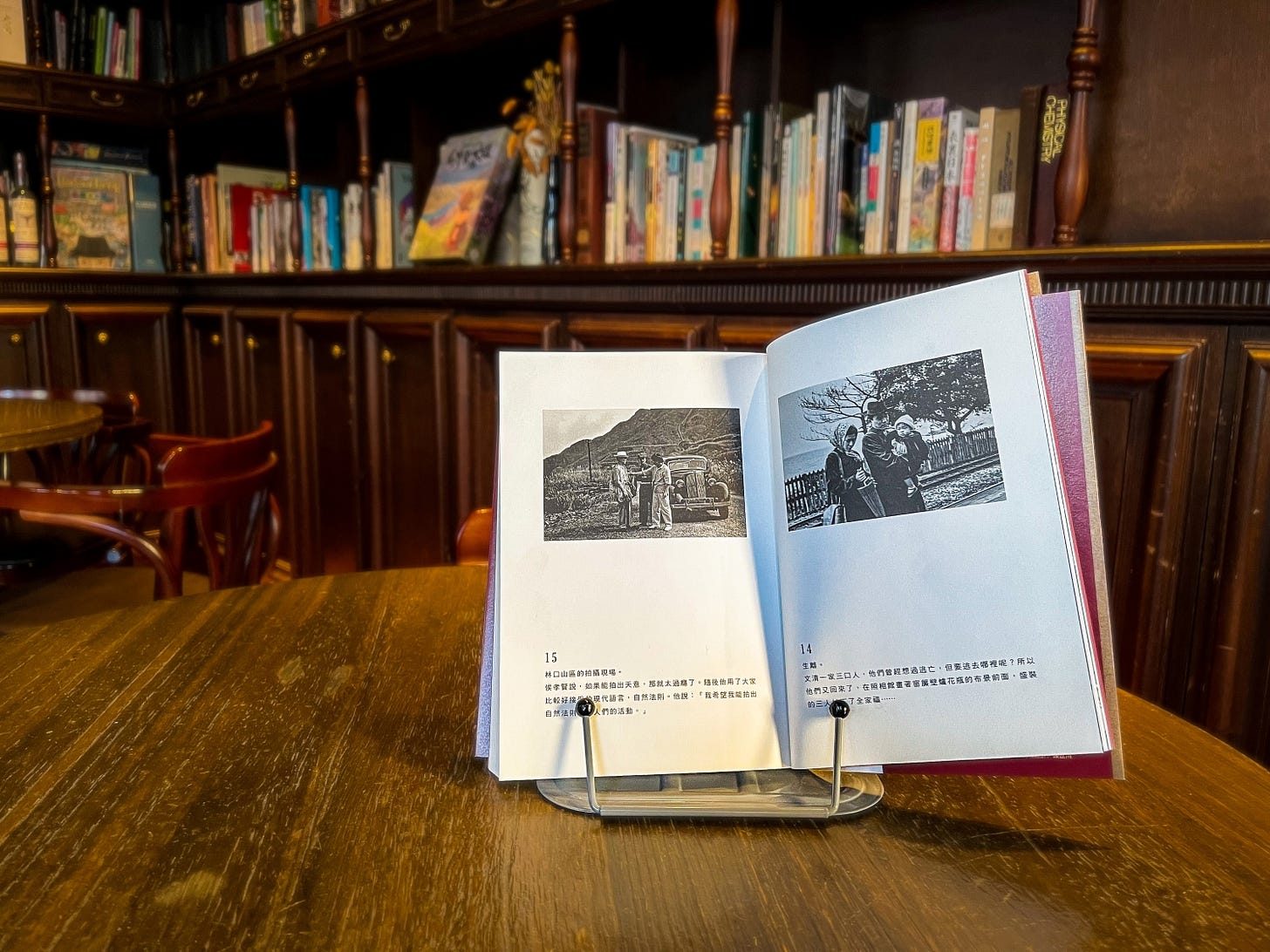

But the remaster of City of Sadness also intersects more broadly with public anxieties about the danger of forgetting. We can see the imperative of remembrance not only in the high-profile re-release of the film, but also in the lasting material traces that accompany the film’s re-release, including multiple handsomely produced volumes about the film, its script, and its production process. On the one hand, these volumes are of course part of the celebration a masterwork of 20th-century cinema. But on the other hand, they also act as a lasting, tangible reminder of the film’s subject matter.

As we’ll see in just a moment, much of the advocacy around 228 today is about getting young people to remember, to recognize, to care about an event that happened more than 75 years ago. Restoring City of Sadness provided an opportunity for large-scale advertising campaigns that feature statements like, “A film that every Taiwanese person must see once in their life” (a statement repeated on the cover of the newly-reissued script and in trailers for the film.) Thus, in City of Sadness, the national imperative of history-making, reflected in the the 4K canonization of Taiwanese films, collides with the national imperative of future-making, in which aspirational visions of Taiwan’s future are contested in the public sphere through a broad repertoire of cultural and political tools.

This repertory of tools was more explicitly on display in the events later in the weekend, both in Kaohsiung, and then in Taipei.

228 as Public Education in Kaohsiung

Thanks to networks of friends, I was alerted to a series of lectures and film screenings in Kaohsiung over the 228 weekend. As such, I boarded Taiwan’s glorious high-speed rail and made my way to the southern port city.

Now, I have wanted to go to Kaohsiung for a while. Faced with confusion on the part of many of my Taiwanese friends, I explain that much of my desire to go to Kaohsiung comes from a very fun Taiwanese mystery show called Black and White 痞子英雄 (available on the website of your friendly streaming overlord), which is in Taiwan’s southern port city, and with which I may or may not have whiled away a significant amount of quality pandemic couch time.

From now on, when people ask me why I want to go back to Kaohsiung, I have much more concrete answers. Top of the list is the Neiwei Arts Center 內惟藝術中心, part of the enormous cultural park in northern Kaohsiung that also houses facilities like the Kaohsiung Fine Arts Museum (and that will make an appearance in a blog post a couple of weeks from now).

Equipped with educational facilities, exhibition spaces, and two state-of-the-art theaters for film screenings, the programming at Neiwei is worth a trip to Kaohsiung in its own right. Combine that with great food, palm-lined boulevards, a statue of a Daoist deity towering several stories above a lotus pond, and a postcard-perfect waterfront district, and Kaohsiung is just the place for a weekend getaway.

On this particular weekend, I spent most of my time in the screening room at the Neiwei Arts Center. I attended two of the (excellent) public lectures hosted by Neiwei, the first of which explored the lives of several Taiwanese high school students who were enrolled at Kaohsiung’s top Japanese high school when the violence from the 228 Incident spread from Taipei to Taiwan’s southern reaches. The second lecture explored some of the vagaries of the Taiwanese government’s stringent laws regulating the distribution, sale, and broadcasting of popular music during the nation’s four decades of martial law.

But the centerpiece of the museum’s programming was a 2021 documentary by Lau Kek-huat 廖克發, Taste of Wild Tomato 野番茄, a haunting work that eloquently mixes languages, musics, and silences to produce an accounting of the ways in which entire lives were shaped by the events following February 28th, 1947.

Once again, silence becomes a theme that connects the experiences of the film’s interviewees. In one case, an elderly man switches between the Taiyu of his youth, the Japanese of his schooling, and the Mandarin imposed upon him following the arrival of the KMT in Taiwan, as he recounts how he and his Taiwanese classmates (a shrinking minority in Taiwan’s elite high schools under Japanese rule) first banded together to protect themselves against the violent bullying of their fellow Japanese students, and later to protect those who took shelter on the school grounds during the peak of the violence. Besides the surprising good cheer with which he sometimes describes the gorier details of the battles that took place between students and authorities, his rapid shifting between languages and occasional search for means of expression is a living reminder of the long-term communicative consequences for a generation that was robbed of its language not just once, but twice.

Elsewhere, a former radio folk music star tells how her music was banned by dint of its Taiyu lyrics. Overnight, she went from a stable living singing on the radio to singing in teahouses, brothels, or even along roadsides as a way to make ends meet. Her improvised performance, though perhaps not as polished as it would have been at her peak, gives vent to the resentments that were long suppressed under martial law.

Another interviewee narrates how her life, along with her elder sister’s, was indelibly shaped by 228. First, her father was killed by stray gunfire. Later, while the girls were still teenagers, their mother was anonymously accused of some impropriety and hauled away, never to be heard from again. Meanwhile, the interviewee’s sister, once a leading 228 activist, is now afflicted with advanced Alzheimer’s, with her stories of agitation for recognition and restitution locked behind a mostly silent façade.

The film is clearly sympathetic with the plight of victims and protestors. Thus, I particularly admire the director’s decision to include footage of one elderly activist who continues to campaign to rename and decommission public sites dedicated to the memory of Chiang Kai-shek. When this activist travels from Kaohsiung to Taipei’s Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall 中正紀念堂 (the very same that looms over my trips to the National Concert Hall and Theater) to protest, he is challenged by a middle-aged volunteer docent. She demands, “Would Taiwan have been better off under the Japanese? Would Taiwan have been better off under the Chinese Communist Party? Who would have come if the KMT hadn’t come?”9

The elderly activist is drawn into an argument that neither side can win. The apparently pro-KMT docent is unwilling to accept that sites honoring the architect of the White Terror (and, according to his own diaries, authorizer of the 228 Massacre) might be a lasting source of pain and insult to victims and their families. The film’s interviewee is unable to deny that life under Japanese rule was not exactly a bed of roses.

On the one hand, the docent’s argument seems to me to be beside the point. Whether Taiwan would have been better or worse under the Japanese or KMT-imposed White Terror is immaterial. What is at stake in the current debate is whether, once the political climate allows for free and open debate, you continue to honor an individual who oversaw a regime responsible for decades of egregious human rights violations, extrajudicial executions, and mass disappearances.

What strikes me as important in this argument, however, is not the content. (Like I said, for the two antagonists, it’s an unwinnable debate.) Rather, this argument shows just how divisive this issue remains in contemporary Taiwanese society. And indeed, the tension between remembrance and letting bygones be bygones was front and center at the final commemoration event I attended.

The Gongsheng Music Festival

The Gongsheng Music Festival 共生音樂節 (GMF) is a large-scale event, now in its 11th year, that has become much more than a music festival. Indeed, one of the first things that struck me upon arriving is that, at the GMF, the 228 Incident has become much more than 228. Rather, the festival brings together musicians, politicians, and a wide variety of activists and organizations engaged in political and human rights advocacy, turning 228 into a site for reflecting on the progress that has been made locally, regionally, and globally in human rights, as well as the many areas in which human rights projects remain incomplete, vulnerable, or in active danger of regression.

In the fair surrounding the stage, one could take human rights quizzes at the Amnesty International booth, get a signed copy of a book by an elderly overseas Taiwanese man that advocates for the perpetuation of the US military presence in Taiwan as a deterrent to Chinese aggression, and as a way of preserving “the longest period without a war in Chinese history.” Vendors selling beverages and food were bordered to one side by pro-Tibet activists, and to the other by booksellers hawking graphic novels set during the White Terror, histories of the 228 incident, and moody black-and-white photography collections. In short, the festival collected around itself a wide spectrum of individuals, organizations, and businesses with connections to human rights activism.

When I first arrived about an hour before sunset, dozens of people were seated on the concrete road reading. Thus, even though the musical performances were already underway at the time I arrived, there was a surprisingly reflective atmosphere. This would ebb and flow over the course of the evening, but never completely evaporated.

The undeniable center of attention was the main performance stage, set up outside Taipei’s 228 Peace Memorial Park, across the street from the Presidential Office Building. Over the course of the evening, the acts that crossed the stage covered a range of genres, languages, identities, and career stages: Khuann Jit Tsa Am 看日早晚 delightfully combined funk timbres with melodica solos in their laid-back opening act; Lei Qing 雷擎 is a young, Latin-infused solo act with a distinctly pedagogical bent to his performance style (he even brought a rain stick to pass around the audience while he performed); a collaboration between the lead singers of Taiyu bands Leather Lattice 皮格子 and Tsng-kha-lâng 裝咖人 brings together two up-and-coming local artists; Elephant Gym 大象體操 (gracing stages at SXSW through today) is major indie group with an international following, yet remains down-to-earth enough that their bassist, KT Chang 張凱婷, was milling amongst the crowd toting a large (steadily emptying) bottle of white wine before going on for her set; Kaohsiung-based Hakka singer Lin Shengxiang 林生祥 appeared on stage with just one other musician from his band, playing what I can only describe as a hybrid between a guitar and a yueqin 月琴, the traditional Chinese instrument named for its moon-like shape; and Panai Kusui 巴奈 庫穗 is a veteran singer-songwriter and indigenous activist, whose previous albums have gained her serious accolades (including a performance at the investiture of President Tsai Ing-wen), and whose commitment to the aboriginal rights at one point led her to spearhead protests for 1,800 consecutive days outside the Presidential Office Building.

Each of the musicians had their own way of addressing the topic of 228. Some, like the musicians of Leather Lattice and Tsng-kha-lâng, tried to draw direct links between their creative process and the social legacies of 228. Lin Shengxiang simply explained that, given the solemnity of the day, he had chosen pieces meant to invoke remembrance and respect for the victims of the 228 Incident and the White Terror. Panai Kusui’s stage patter dwelt mostly on 228 in the context of Taiwan’s ongoing social activism (that is, when she wasn’t chastising the tech booth for fiddling too often with the stage lights). And, in a seemingly off-the-cuff but almost-certainly-rehearsed bit of dazzlingly witty stage banter, the brother-and-sister brains behind Elephant Gym took a series of cracks at voters who elect people based on how they look rather than what they say and do.

This last gag is a clear dig at the newly elected mayor of Taipei, Chiang Wan-an 蔣萬安, who is both one of the more photogenic members of Taiwan’s political class and, for many in attendance at the music festival, the living embodiment of the state-sponsored terrorism of Taiwan’s White Terror. You see, Chiang Wan-an claims to be the illegitimate great-grandson of former dictator Chiang Kai-Shek. This also makes him the purported grandson of Chiang Ching-Kuo who, depending on your political persuasion, is either remembered for lifting martial law or for leading Taiwan’s secret police during (you guessed it) the White Terror.

Chiang claims to be of a more moderate bent than his ostensible forebear (although, to be fair, this would be a rather low bar to limbo under). He bills himself as a technocrat who cut his teeth in Silicon Valley venture capital, rather than as a veteran of brutal military conflicts. But although Chiang downplayed his links to the Generalissimo in his recent mayoral campaign, this tabloid-fodder baby-daddy tale gets more complicated, and highlights the lasting power of the Chiang name to elicit both veneration and vitriol.

You see, the main branch of the Chiang family has acknowledged the relationship with neither Chiang Wan-an nor his father. Furthermore, both disputed members of the Chiang family were born with the surname Chang, only changing their name in adulthood. Thus, for many opponents of the newly appointed mayor, this is not simply a matter of a latter-day member of a political dynasty joining the family business. Rather, for his detractors, the active choice to change his name to that of Taiwan’s decades-long authoritarian ruler represents an opportunistic and cynical attempt to capitalize upon the most in/famous name in Taiwanese politics.

But I digress. Let’s get back to the concert!

Music, Taiwanese Identity, and the Future of Remembrance

One of the big questions that always comes up in events like the GMF is, “What good does a concert do?” Indeed, my friend’s Taiyu teacher, who was in attendance to see her grandson perform, felt that the atmosphere at the event was not nearly solemn enough. More generally, musicians and artists are often accused of meaning well, but having little to offer in the way of actionable advice.

One fellow concert-goer with whom I started talking said that, in her opinion, this was an effective event, but mainly because most of the people who were attending were already interested in the legacies of 228. In her opinion, those who weren’t interested beforehand would probably just stay home, especially given the concert’s very explicit politics. And while she acknowledged that there might be some people there to simply to support “their” bands, she felt that those in attendance for the sake of the music alone most likely made up a shrinking minority of the audience.

Although each of the bands addressed the issue of 228 in their own way, I thought that the comments that made the greatest case for music and the arts as a public site of remembrance came from the two politicians who spoke at this event. One of those, the federal legislator Miao Po-ya 苗博雅, is well known for her queer activism and her pro-independence stance. She has also been present at all 11 years of the GMF.

In a fiery 15-minute speech, Miao largely stuck to familiar territory: Taiwan should be free to be Taiwan; the KMT should adequately address past atrocities, including assigning official blame; screw the critics who argue, “Why do you still need to stand up and commemorate this day? Why do you constantly have to exploit 228? Why do you want to create such divisions among the people? Why do you want to create so much hate? Why can’t you give it a rest with the blameless Mayor Chiang Wan-an?”10 (The latter statement drew cheers from the admittedly partisan crowd.)

But she went on to explain that her reason for memorializing 228 is not because of trying to ban political parties or prevent particular people from running for office, none of whom were born in 1947. Rather, she argues that the memorialization of 228 gives us an opportunity to move past the simple commercialism of Taiwan’s booming consumer and entertainment cultures (always strongly on display during long holiday weekends like this one), to continue to find explanations for the injustices and events that have not yet been made clear, and to offer victims whose stories have not yet been told an opportunity to be heard.

Even more, though, Miao singles out what she sees as the double speech of the government, as well as official explanations of the causes and authorizers of the 228 Incident and the White Terror. “On the one hand, we say to all the victims and their families, ‘We apologize.’ Then the next day we stand in front of the mausoleum of Chiang Kai-Shek or [his son] Chiang Ching-Kuo with eyes red from weeping to recall, to cherish the memory of, and to commemorate these kinds of dictators. We will forever say, ‘Taiwan supports the Ukraine,’ while our national concert hall invites the soprano who is personal friends with the dictator Putin to come and perform in Taiwan.”11

For Miao Po-ya, the struggle to bring 228 to light is ultimately a struggle between becoming “a nation that remembers, or a people that can’t make sense of anything.”12 For her, the function of events like the GMF—and the purpose of inviting friends, classmates, and colleagues to future events—is so that “together, we can turn Taiwan into a country that knows why it has fallen, and also knows what it needs to do to stand back up.”13

Though Miao Po-ya’s rhetoric was forceful, and though it is clear from her long engagement with the GMF that she is convinced of the value of memorial events like these, it must be admitted that her talk was light on details about what exactly music provides (her Anna Netrebko reference aside).

In contrast, Freddy Lim 林昶佐, the former president of Amnesty International Taiwan, the founder and lead singer of Asia’s most famous heavy metal group Chthonic 閃靈, and second-term representative in Taiwan’s Executive Yuan, provided a much more concrete vision of the concrete long-term contributions of events like the GMF. (For any curious readers, the video below is the first single Chthonic has released in several years, timed specifically to coincide with February 28th.)

Lim’s talk, like Miao’s, was delivered in a casual-yet-preppy outfit (an astonishing removal from his days as the front-man of a heavy metal band). Unlike Miao’s, it moved fluidly between Mandarin and Taiyu. Also unlike Miao, Lim focused broadly on the arts, appropriate for a speech that was punctuated by fans in the crowd singing his own lyrics at him.

Lim started with a reference to Germany. He noted that it’s strange, even 80 years after the end of WWII, that very few people complain when they see another new play, book, or movie about the Nazis. (To his point, one of this year’s film awards contenders, All Quiet on the Western Front, tackles another war of German aggression, albeit in a way that faces criticism for being overly sympathetic in its portrayal of Germany.)

In contrast to the general acceptance of artworks focused on Nazi Germany, Lim argues that revisiting the history of KMT atrocities tends to elicit the refrain, “How is this back again? Enough, already!”14

Lim goes on to develop his comparison with Germany through the example of contemporary popular culture. He asked if audience members knew how the character the Mandarin, the villain in both the Shang Chi comics and in the blockbuster film Shang Chi: Legend of the Ten Rings first appeared in the comics. “When Marvel started to paint the villain the Mandarin, the character was in hiding as a member of the Kuomintang army … So when we talk about the KMT resembling villains, even foreigners pick that out and say, ‘Hey, this is a great model for a villain!15 In all the world, in addition to the Nazis, there are all kinds of actual historical villains that we can turn into the bad guys for our superhero comics and movies. I can pick them out and create villains from them.’ But not Taiwanese. Taiwanese will elect them as mayor.”16

Lim could have left this as just another dig (definitely in contention for zinger of the night) at Taipei’s newly elected mayor. But he ultimately circled back around to art’s role in the contemplation and understanding of past atrocities and traumas. To Lim, the arts provide a site from which to evaluate history from a variety of angles, allowing different perspectives and different understandings of these events to flourish. In this way, events like the GMF are not simply self-indulgent reworkings of settled history. Rather, they provide avenues to understand how a nation’s history affects its present and shapes its future.

Arts at the Intersection of History

Ultimately, I see Lim’s articulation of artistic production at the nexus of past, present, and future as providing a thread that connects his statements with made by Miao and many of the artists on stage: Miao’s statements about memory as Taiwan’s path to knowing “why it has fallen, and … what it needs to do to stand back up;” Elephant Gym’s riotous but pointed commentary on electing people based on their looks; or Lin Shengxiang’s decision to allow the emotional valence of his repertoire choices to speak on his behalf. All of the participants tried in the their own way to articulate what a 40-year history of martial law means for Taiwan’s present and future.

On the one hand, events like the GMF allow for the variation in pace, timbre, texture, and mood that is required to sustain audience members’ attention over a long evening of commemoration and reflection. Put bluntly, it’s just good programming.

On the other hand, Lim’s comments also point to another purpose of the arts in the process of remembrance.

As the immediate memories fade, and as the generations who directly experienced atrocities like the White Terror pass on, complacency becomes a danger: it’s over and done, it’s settled history, “How is this back again? Enough, already!”

But government agencies continue to block access to many of the state archives around the White Terror. The legal and extra-legal mechanisms that facilitated the abuses and atrocities of Taiwan’s long period of martial law remain murky, at best, and at worst opaque. In this kind of environment, it can become difficult to ascertain if subsequently enacted legal guardrails are adequate to prevent future occurrences. But if the White Terror is relegated to settled history, any drive to establish legal and constitutional guardrails also loses urgency.

Most artists, it is safe to say, hope to elicit an emotional response from their audience members. And while there is some dispute about the historical facts—how many people died? was governmental paranoia justified? has the KMT fulfilled its self-appointed obligations in relation to Taiwan’s process of transitional justice?—the artists of GMF are, in the main, not arguing about historical facts. This is not Kellyanne Conway’s “alternate facts,” Tucker Carlson’s “peaceful tourists,” or Alex Jones’s hateful conspiracy theories.

Rather, what each of the artists, speakers, and organizers of the GMF seem to be attempting is to create new emotional associations with the events of 228 and the decades that followed. In so doing, the explicit goal for many of these participants is to sustain existing will (or to create new political will) to finish the still-incomplete work of restitution and reconciliation.

I have rambled for a very long time about a very somber topic, and if you’ve made it this far, you deserve an award. As such, I’ll wrap things up here. But not before saying, when people argue about the political role of the arts in general and music in particular, I would suggest that the point is rarely whether music, film, or theater are suitable vehicles for promoting mass awareness of historical facts. (Spoiler: they rarely are.)

It is in fact the ability of the arts to evoke emotions, to create strong feelings in audience members, and then to link those feelings to the political life of the nation that defines the role of the arts in the political life of the nation. As the world watches the rise of Russian propaganda, Chinese nationalism, and the American inability to agree on the basic facts of reality, we would do well to consider the role that the arts play in stoking the emotions that cloud rational thought and critical reflection, as well as the counter-emotions that committed artists are trying to invoke as an antidote to these phenomena. And we would do well to find the political will to address these issues with urgency and clarity, before our own archives are quashed, before our courts block avenues for legal recourse, and before the damage done to the institutions that have perpetuated liberal democracies around the world becomes unsalvageable within our lifetime.

Hsiao-ting Lin, Accidental State: Chiang Kai-shek, the United States, and the Making of Taiwan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016): 45.

Craig A. Smith, “Taiwan’s 228 Incident and the Politics of Placing Blame,” Past Imperfect vol. 14 (2008): 150.

Gary D. Rawnsley and Ming-Yeh T. Rawnsley, “Chiang Kai-shek and the 28 February 1947 Incident: A Reassessment,” Issues & Studies, vol. 37, no. 6 (November/December 2001): 77-106.

Lin, Accidental State, 47.

Lin, 47.

After some mild Googling, it seems that Taiwan’s unenviable record was subsequently surpassed by Syria. Nevertheless, at the time that martial law was lifted in Taiwan, it appears that this statement was true, and this fact continues to hold currency amongst 228 activists.

For a great discussion of the role of trauma in the contemporary Taiwanese cultural sphere, see Sylvia Li-chun Lin’s Representing Atrocity in Taiwan: The 2/28 Incident and White Terror in Fiction and Film (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007).

Correction: I previously mistakenly said that Wenqing threw the pen. Upon reviewing the scene, I see that he punches the table, but does not throw the pen.

As I’m operating from memory, this is a paraphrase.

“為什麼在今天還要站出來紀念這個日子?為什麼要不斷地消費二二八?為什麼要不斷地撕裂族群?為什麼要製造這麼多的仇恨?為什麼不能放過無辜的蔣萬安市長?”

The March 5th solo performance by Anna Netrebko that Miao referenced here was subsequently cancelled after protests from members of the public, a decision that was widely reported in local, regional, and international media, as well as opera industry publications.

Original quote: “一邊對所有的受難者跟遺族說「抱歉」。然後改天去到蔣介石跟蔣經國的靈寢前面,紅著眼眶流淚、懷念、紀念、緬懷這樣的獨裁者。我們永遠會說出,一邊說「台灣支持烏克蘭」,另外一邊我們的國家音樂廳邀請跟普丁獨裁者是好朋友的女高音來到台灣表演”。

“這個鬥爭是我們要成為有記憶的民族,或者是一個什麼都搞不清楚的一群 人的鬥爭”

“我們一起好好地讓台灣成為一個知道自己為什麼跌倒,而且知道要怎麼樣站起來[的國家]”

“啊怎麼又來了啦?啊夠了沒啦!”

This statement elicited the extremely vulgar shout from an audience member, “Motherfucking KMT” 幹你娘國民黨.

Elsewhere, media has reported that the Mandarin, the main villain in Shang Chi: Legend of the Ten Rings, and one of the villains in the Marvel comics on which the film was based, was actually based on the racist stereotypes of the supervillain Fu Manchu, created by Sax Rohmer. In relatively cursory perusals of Marvel fan websites, I have not been able to find reference to the Mandarin’s career in the KMT army.

Update: Many thanks to Justin, who delivered definitive proof of the Mandarin’s KMT connections, straight from the Marvel-ous horse’s mouth.

Original quote: “漫威開始畫到滿大人這個惡棍的時候,他是躲在山區的國民黨軍閥⋯⋯所以像國民黨這樣子的惡棍跟敵人,連外國人都會把他拿來說「欸,這是一個很好的壞人的原型」。然後,除了納粹意外,世界上還有好多種壞人,可以拿來做我在這個拍、或者在畫超級英雄的這種漫畫的時候,可以有好多歷史上曾經發生過的壞人,我都可以拿來做創作。但台灣人不是啦,台灣人會把他選成市長.”