They Look Great for Their Age (But They've Had Some Work Done)

4K Remastering as Filmic Repertory

Warning: I’m not sure how coherent today’s post is going to be. I’m in the midst of my first cold since 2019, and it’s a real humdinger. I’ll try to keep today’s post mostly cogent, and hopefully I’ll be back next week at full strength!

Background information 1

At music school, genealogical connections to Haydn are a real flex. The number of violinists that can tell me their degrees of separation from Haydn down to the nanosecond is astonishing. Not to be out-genealogied, the number of singers that can trace their pedagogical lineage back to the likes of Manuel Garcia or Pauline Viardot is similarly manifold.

Of course, if being 7 or 11 or 28 teachers removed from Haydn or Viardot or Garcia gives one some mysterious artistic authority, then we all deserve an Oscar (per Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon).

My skepticism notwithstanding, this is a relevant piece of background trivia for today’s hand-wringing session.

Background information 2

When I first got out of quarantine in Taiwan, I was crushed to discover that I had missed a Leslie Cheung 張國榮 retrospective during my time safely locked away from the rest of Taiwan’s population. Cheung is best known in the West for his star turn in Chen Kaige’s 陳凱歌 Palme-d’or-BAFTA-Golden-Globe-winning film Farewell My Concubine 霸王別姬, but his filmography runs far deeper than that, and is preceded by an extensive discography. Perhaps more important to me personally, he was an early queer icon here in Asia, and his suicide shone a light on the struggles of Asia’s queer community at a time when the issue remained largely taboo.

The posters for the Cheung retrospective stayed up for quite a while—spitefully so, it seemed to me. As such, I was given ample opportunity to prod at my disappointment. What I hadn’t realized is that the Leslie Cheung retrospective wasn’t a one-off, but rather part of a wider phenomenon of retrospectives and 4K “restorations” of classic films. And many of these re-releases are Events with a capital E, complete with commemorative tickets, photographs, and other swag.

Ultimately, I began to feel some resonances between the phenomenon of 4K restorations and the conservatory genealogical flex that characterized so much of my education. And even though wiser heads than mine will probably be able to point out all the reasons these are most definitely not the same phenomenon, I’m nonetheless going to clutch at these pearls for the rest of today’s post.

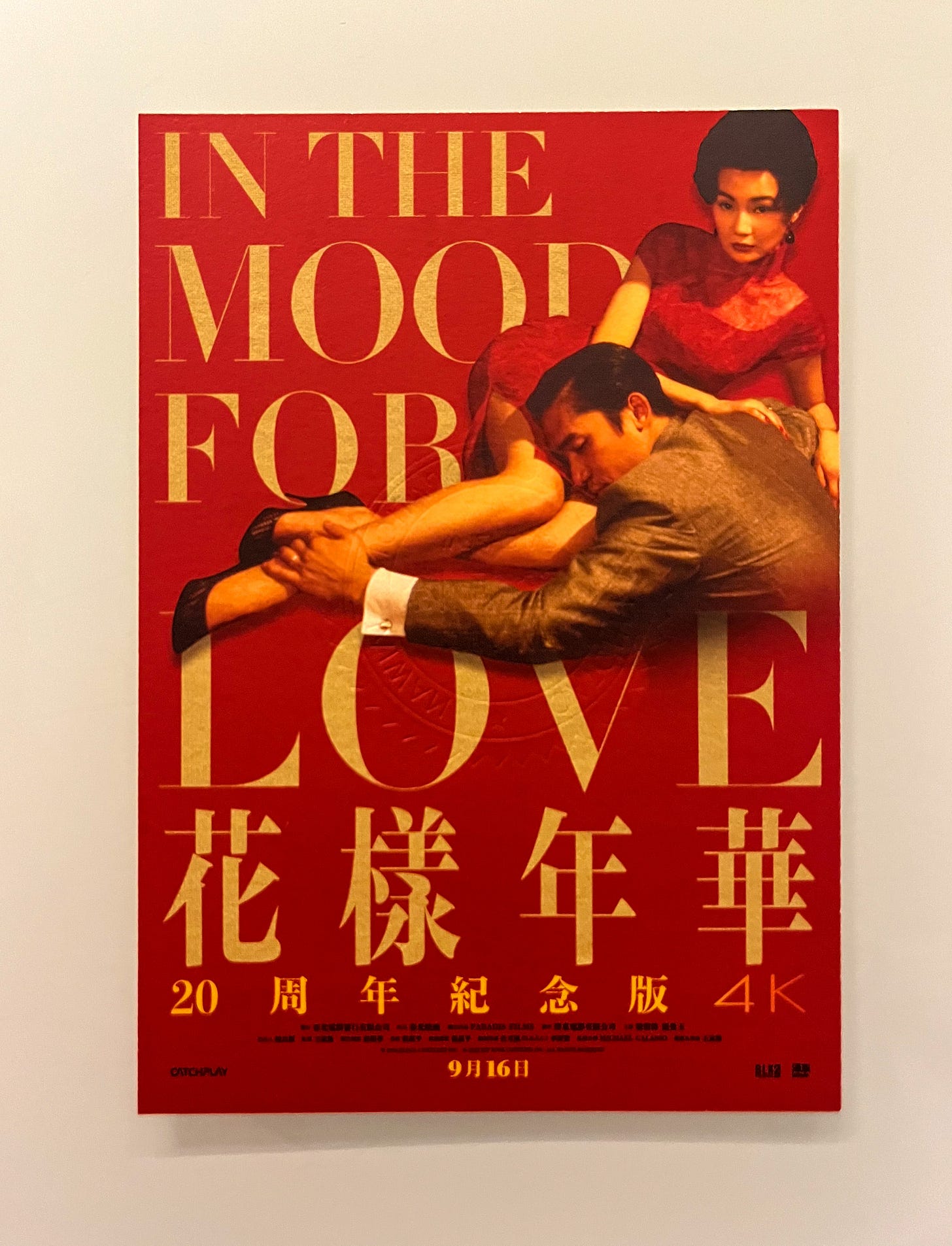

Remaster as Werktreue

A lot of the remastered films that I’ve personally seen here in Taipei are the classics of East Asian cinema: the stiflingly sultry In the Mood for Love 年樣年華 by Wong Kar-Wai 王家衛; Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s 侯孝賢 brutally unsentimental account of young men from the wrong side of the tracks trying to get ahead in life, The Boys from Fengkuei 風櫃來的人; Center Stage 阮玲玉, the Stanley Kwan 關錦鵬 documentary-biopic mashup about Ruan Lingyu 阮玲玉, China’s first bona-fide movie star; a makeover of the visually sumptuous steampunk anime (with occasional hints of space opera), Vampire Hunter D; and most recently a monumental, two-part documentary called The King of Wuxia, about the martial arts film director King Hu 胡金銓, which combines documentary film techniques with newly restored clips of the director’s films.

Now, from my layperson’s perspective, films are usually a sort of one-and-done affair: they’re shot, they’re edited, they’re released, they’re done. Maybe in some cases you also get a director’s cut. But the point is, in my head a finished film is a finished film, a fixed text.

What I find interesting in this wave of 4K remasters is that, to a certain extent, the process of “restoration” or “remastering” unfixes the completed work. It turns the finished film into something that can be remade (or re-performed, if you will) for contemporary audiences. And it affixes new names to the film—the directors in charge of the remastering process, the colorists, the technicians, the institutes that sponsor the remake.

This phenomenon bears an interesting resemblance to the classical music fetish for Werktreue—the idea that the good musician is simply a faithful executor of the composer’s wishes, as encoded clearly and unambiguously in a fixed, unchanging score.

Werktreue is itself a myth, of course. Many of the world’s most beloved “fixed,” “unchanging” scores are the result of countless hours of scholarly labor that piece together a single, representative version of a work that usually exists in a number of different forms. You like it when the tenor in Don Giovanni sings both “Il mio tesoro” and “Dalla sua pace”? Tough, they weren’t written for the same person or the same performance. You think Mozart’s masterpiece is the Requiem? Tough, it was completed posthumously by his student. You like the soprano’s “Rejoice” aria from Messiah in 4/4 time, with lots of bubbly 16th notes? Tough, it was originally written in 12/8, and those are triplet eighth notes, not 16th notes.

But wait, the tenor in Don Giovanni often does sing both arias. The Requiem is marketed as one of Mozart’s masterpieces. And who (except for Sylvia McNair in the above video) sings “Rejoice” in 12/8 nowadays?! As is so often the case, there tends to be a way to craft Werktreue into a narrative that *just so happens* to *completely coincidentally* conform to pre-existing industry practice.

How exactly is Werktreue connected with 4K remasters? Well, one place I see the two overlapping is the fact that many of these remasters were completed with “consultation” from the original director. (Note the artful phrasing: not “under the direction of” or even “under the supervision of” the original director, but with their “consultation.”) This directorial stamp of approval, however tenuous, is clearly a strategy for signaling faithfulness to the original work.

Elsewhere, this goes even further. For example, the remastered version of The Boys from Fengkuei makes a point of the fact that the shortcomings in the original audio were left unaltered, so as not to distract from the original viewing experience. In this sense it becomes a masterpiece like Beethoven’s 9th symphony, which has some flaws-but-not-really. And being a masterpiece, nothing in the original text should be changed (except for the bits we’re going to change, of course, so please do buy a ticket.)

Classicizing Film

What I find interesting is the way the 4K remaster phenomenon reflects an increasingly canonized film corpus, not just in East Asia, but globally.

This has long since happened in Western classical music. One of the effects of this canonization is that we don’t just have the Goldberg Variations, we have Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations. We don’t just have “Casta diva” from Norma, we have Maria Callas’s (or Joan Sutherland’s, or Montserrat Caballe’s, or Angela Meade’s, or whomever’s) “Casta diva”. We don’t just have Magic Flute, we have Julie Taymor’s Magic Flute.

This isn’t to say that classical music is the only place where this happens. Popular musicians are constantly covering the works of their peers and predecessors—for example, Nat King Cole’s American-accented cover of “Quizás,” which features prominently in Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love. Revivals are common enough on Broadway that revivals of musicals and plays have separate Tony Awards categories. And of course, there’s the Royal Shakespeare Company, whose name sort of gives away the source of the troupe’s bread and butter.

From a layperson’s point of view, it seems to me that contemporary cinema is going through a process of classicization that has long since passed in Western classical music, jazz, Peking opera, and theater. And it’s not a process that’s isolated to 4K remasters. There are the franchises whose futures legions of fans worry about (James Bond, Dr. Who, Star Wars). There are the sequels (Sister Act II: Back in the Habit, season three of Twin Peaks [a mere 25 years after the original], and countless Marvel and DC films). There are the remakes (Ocean’s Eleven, live-action Disney, or recent lightning rods like Netflix’s live-action Cowboy Bebop). And there are the stage-to-screen crossovers (Chicago, Into the Woods, Mamma Mia!, Sweeney Todd).

There’s plenty of chatter about how Hollywood is out of ideas, how too many directors are sellouts nowadays, about how movies are all focus-grouped to death before they ever hit the cinema. And some of that may be true. But I also wonder if this is as much about an industry that is ever more keenly aware of the weight of history, of the buildup of a canon of masterworks that is constantly looking over the shoulder of aspiring young directors and actors.

Or is this about a group of industry professionals who want to pay tribute to the works that got them excited about film in the first place and inspired them to pursue careers in the cinematic arts? Just like musicians tracing their artistic lineages back to Haydn and Garcia and Primrose and Boulanger, is this about establishing and honoring an artistic legacy, not only as a set of empirical facts (after all, some of the links to Haydn may have grown in the retelling), but also as a legitimating springboard for the imaginative reworkings and reinterpretations that are the lifeblood of Western classical music as it exists today?

I haven’t interviewed anyone about this, and I probably won’t, so instead I’ll just leave you with those wildly leading questions.

But if I flog this classical music analogy past the point of expiration, it seems to me that we can see in the flood of 4K remasters many of the same impulses that characterize the lineage-obsessed, Werktreue culture of Western classical music. The desire to establish and defend a (frequently nationalist and/or exclusionary) canon. The desire to maintain—or even increase—the relevance of that canon as time passes. The desire to use lineage to legitimate modern “performances”—that is to say restorations, remasters, or remakes. But perhaps most importantly, the desire of later generations to connect themselves to and put their own stamp on the works that originally inspired them to join a creative field.

Does that mean that the canonization of film will lead the industry down the same road as an all-too-often moribund classical music industry that struggles to move past Bach and Brahms, Mimi and Manon, Die Hebriden and Ein Heldenleben? Not necessarily. For one, there is still greater demand for new content than in classical music. For another, without completely redoing them, films as texts are ultimately more fixed than musical scores.

But it does suggest an interesting substrate layer to contemporary cinematic arts. For all that we claim to value creativity, uniqueness, and revolution in filmmaking, the increasing trend towards remakes and restorations suggests a pervasive desire to revisit recognized masterworks.

This then provides a counterpoint to the ongoing discussions in classical music about how we might balance works of the past, both canonical and lesser known, with the exciting new works composers today are producing. Can classical music organizations mine a film industry model in which a 4K remaster of In the Mood for Love can live alongside a sequel like Thor: Love and Thunder and an original work like Everything Everywhere All at Once for inspiration? Put differently, does this provide an alternative analytical frame for classical music organizations who know that change is necessary, but who find themselves drowning in their own Kool-Aid?

Of course, none of this takes into account existing institutional structures, economic interests, donor pressures, training pipelines, or any of the other myriad problems that always get in the way of producing meaningful change. Luckily, that’s all above my pay grade, so I can go back to watching my 4K remasters.

Next up: The King of Wuxia, Part 1. Just as soon as I get over this stupid cold.