Today’s post is a bit longer and a bit more academic than usual. So if you’re here mainly for the drinks recommendations, feel free to skip ahead to the third section of today’s post. Also, most of the fun pictures are in the second half of this post, if that’s what you’re here for. :)

I recently had the pleasure of attending a guided tour of Dadaocheng 大稻埕 hosted by the Lehu Project 樂乎計劃. Among the events that they hosted was a demonstration tea ceremony at Ing Lok Tshun Hong Formosa Tea 永樂春風, one of the flagship spaces of the commercial group that has led the transformation of Dadaocheng in recent years.

This experience, lovely though it was, got me wondering: what is the role of tea in Taiwan today, not as a beverage, but as a symbol? It’s clearly a source of national pride, with people of all ages and backgrounds telling me definitively that Taiwan’s tea is the best in the world. But it also serves as a vehicle for a romanticized, “all’s well that ends well” telling of history.

So today we’re going to talk about tea, and the way it seems to live in Taiwan’s national imaginary somewhere in the grey zone between branding, nationalism, and (self-)stereotyping. How am I going to talk about tea? Well, I’m going to start with a tea ceremony demonstration that I recently had the pleasure of attending. And then, because I finally gained access to Tai-Pak 台北 (the watering hole where I and my colleagues were turned away a few weeks ago), we’re going back to the bar, baby!

But first, a bit about symbols.

Of Nations and Symbols

Nationalism relies on symbols. By symbols, I don’t just mean anthems, flags, capitol buildings, or famous landscapes.1 I also mean those symbols that are plucked from society and made to carry the weight of national identity. These are the “invented traditions” that help to form the national imaginary.2 The “age-old holiday” of Thanksgiving,3 the almost global reach of the white wedding dress, or the genre known as Chinese dance—which creatively draws on resources as old as the Dunhuang cave paintings to reconstruct and reimagine traditional Chinese art dance4—could all be considered invented traditions.

Sometimes these symbols have some truth to them—the Swiss really are proud of their cheese, the Great Wall really is an icon in China, and mariachi has a real claim to being Mexico’s national music.5 Other times, these symbols drift perilously close to stereotyping. Thus, although there may be a certain degree of “rueful self-recognition” for Greeks accused of forcefully hurling flatware at the slightest hint of a party,6 or for Japanese who grow weary of reminding people that Japanese cuisine doesn’t stop at sushi, stereotypes like these also point to the ways in which symbols are a double-edged sword. This is even more true for nations that lack the global media clout to control the narrative around their own identity.

Teatime in Dadaocheng

The Place

Now, Dadaocheng looms large in the public awareness in Taiwan. Dating back to the Qing era, it evolved first as an important site for rice processing (indeed, the “dao” 稻 of Dadaocheng points to the district’s rice-based roots). Later, after the Treaty of Tianjin forced open Chinese ports, including the northern Taiwanese port of Tamsui, the Scotsman John Dodd became Taiwan’s first exporter of tea. When a shipload of Dodd’s “Formosa Oolong” arrived in New York City in 1869, it turned tea into Taiwan’s first luxury export. At its peak, the district played host to over 200 tea exporters.

Eventually, Dadaocheng became an important center for Taiwanese intellectuals during the Japanese period, and the incubator for Taiwan’s nascent modern arts scene in the early 20th century. Indeed, the nostalgia-heavy story of the (very popular, very soapy, and very fabulous) TV series La grande chaumière violette 紫色大稻埕, the Chinese title of which means “Purple Dadaocheng,” centers around the artists, tea dynasties, and intellectuals of the district.

In the latter half of the 20th century, Dadaocheng fell into disrepair. The buildings—mostly old and built of brick—are not necessarily where you want to be when “the big one” hits. In the early 2000s, however, fearful that someone would pave Dadaocheng and put up a parking lot (so to speak), a local entrepreneur began to restore the historic buildings of the district, and to recruit businesses to move into the newly refinished spaces. The result has been both rejuvenation and gentrification, with the district’s ritzier, boutique spaces slowly driving out the decidedly less glamorous wholesale businesses that used to be the mainstay of the district.

The Tea

The Ing Lok Tshun Hong teahouse is one of the businesses that moved into Dadaocheng’s newly restored spaces, and it is where a tea master named Sue-Ann led our group in a tea ceremony.

Sue-Ann is impressively credentialed, certified in both Chinese- and Japanese-style ceremonies. She started her demonstration by stating in a joking-not-joking kind of way that Taiwan has the world’s best oolong tea, and that this wasn’t her opinion, it was just the rules, thanks.

Sue-Ann went on to perform multiple rounds of tea brewing, instructing us on how to aerate the tea, how to enjoy its aroma, and how to appreciate the way that the tea’s flavor evolves across successive brewings. She stressed that this was a traditional, Chinese-style ceremony (though, due to time constraints, she didn’t really explain what that meant), and at one point even told us that we were being too quiet—a Chinese tea service should be a much more lively (熱鬧) affair than its solemn Japanese counterpart.

But as she started to explain a bit more, she actually confessed that it was primarily the brewing methods—the leaves, timings, temperatures, etc.—that were Chinese. Many of the trimmings for her demonstration—the table runner, the flower arrangement, and even her gestural vocabulary—were drawn from her training in Japanese tea ceremonies, as she wanted to create a “Zen” effect (something she certainly accomplished, and which might also explain her spectators’ initial reluctance to talk!)

So here we have one version of tea: the flagship product of one of Taiwan’s historic-sites-cum-tourist-attraction, reimagined as a luxury good that can compete for attention with the district’s boutique shops and cute eateries, while simultaneously giving access to an “unmediated taste” of Taiwanese history.

This sounds great, right?! Well, hold on.

Teatime in Da’an

Before I go on: A few weeks back, I promised to report back on the soundtrack of the Village Mouth, and to take another stab at gaining access to the swanky, Cold War-themed bar, Tai-Pak. For the first part, I regret to inform you that the electric fans at the Village Mouth were still going full blast, I still don’t really know what the restaurant’s soundtrack sounds like, and I’ll have to go back again to eat delicious noodles once cooler autumn weather arrives and the fans get turned off (sorry folks, this is how science works, I don’t make the rules).

Tai-Pak, however, was a different story altogether. First of all, though it kills me to admit it after effectively being turned away at the door on our first, abortive visit … their drinks are amazing.

Second of all, to paraphrase my colleague Aaron’s observation from a few weeks back, “it’s not very Cold War-forward.” In fact, the Cold War really isn’t thematized beyond the hand-grenade themed cocktail we sampled (more on that momentarily).

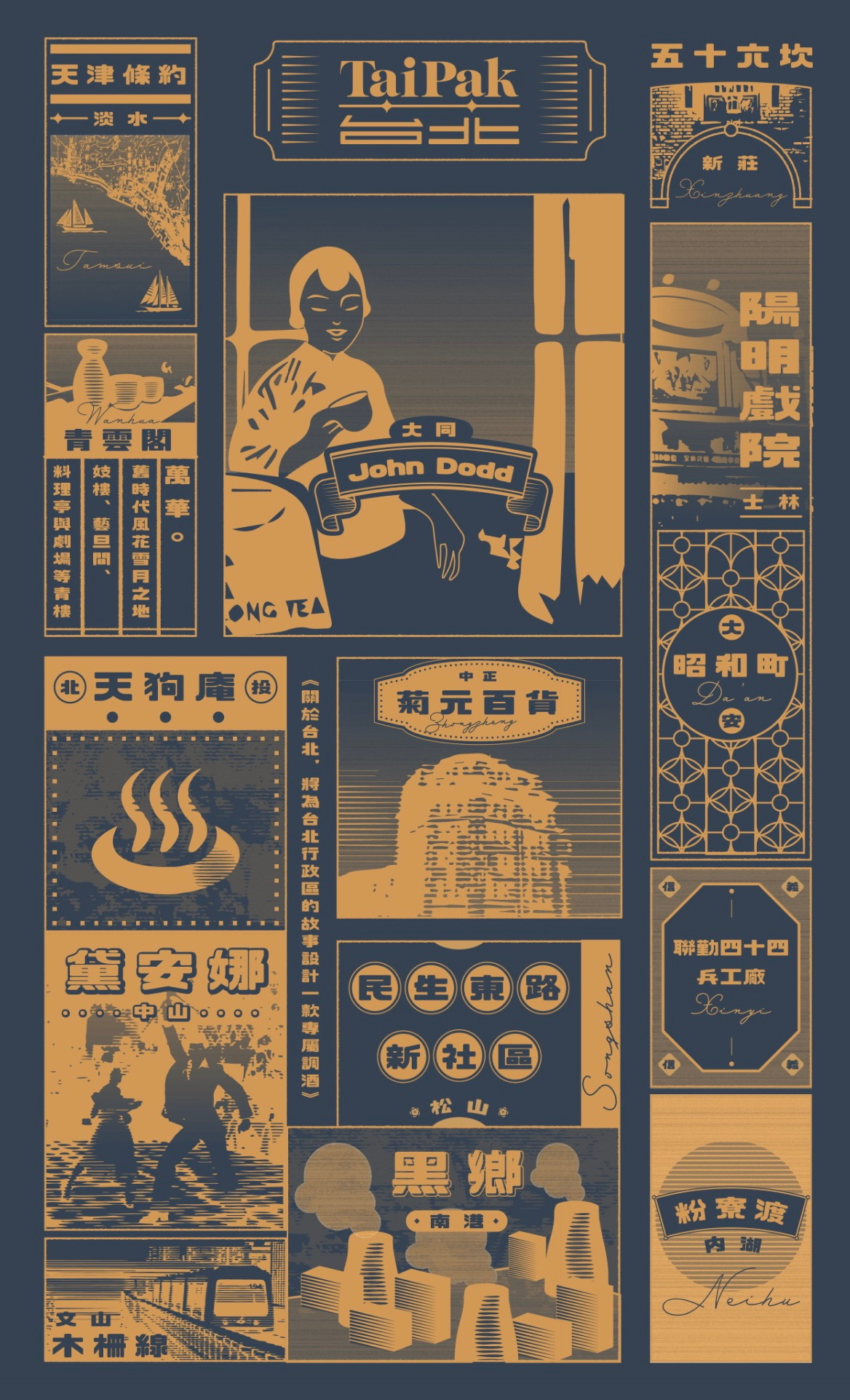

What does come out over and over, however, is the bar’s particular vision of Taiwanese history. This starts from the moment you access the menu by scanning the QR code, handsomely printed on the ceramic coaster sitting next to the stylish Art Deco napkin holder that is currently available in the clearance bins at Ikea.

Tai-Pak’s menu is proof that I have been to the future, and the future is an aesthetic triumph, people. The menu is a gamified technological marvel that is as UI-aware as it is beautiful. (You can scan the QR code in the photo if you want to see for yourself.)

The cover (well, landing page) of the menu is a pastiche of images related to Taipei’s history, clearly selected for their historical significance. Starting in the top left, ships approach Taiwan’s coast, sailing under the heading of “Tianjin Treaty” 天津條約. In the bottom left, Taipei’s first disco sits alongside the “Black Village” 黑鄉 of Taiwan’s old coal-mining and tire-production center of Nangang 南港. In the center right, there is the (enchanting) 44th Arsenal of Combined Logistics Command Factory 聯勤四十四兵工廠. And occupying pride of place, is none other than our tea merchant John Dodd, complete with silhouette of a satisfied customer enjoying a cuppa.

Each of the drinks is associated with a specific neighborhood—the Arsenal is named for the now-trendy Xinyi 信義, the disco is named for Zhongshan 中山 (of Light the Night fame on this blog), and John Dodd is ensconced in Datong 大同, the modern district that encompasses (you guessed it) Dadaocheng. If you swipe on the menu, tiles are revealed. Swipe in one direction and you’ll see the drink name and ingredients; swipe in the other, a brief historical blurb about the district.

And yet, historical awareness in these blurbs largely ends at the barest of facts about the cocktails’ namesakes. The Treaty of Tianjin is simply credited with “contributing to the Danshui district’s most prosperous period.” The Black Village merely mentions that the district’s nickname was the result of air pollution caused by industry. And the 44th Arsenal is noted merely for the fact that it drove housing demand in the area. Cards that come out with the drinks provide slightly expanded blurbs—the 44th Arsenal’s hand grenade production, or the Black Village’s coal mining under Japanese rule—but the links between history and cocktails remain mostly opaque.

Instead, history at Tai-Pak becomes a set of interesting soundbites that anchor a bar’s claims to local authenticity, without getting in the way of a virtuosic display of modern mixological panache. Even the bar’s name, Tai-Pak, is a claim to local identity—“Tai-Pak” is the pronunciation of Taipei in the local dialect. And yet, and no point is this nod to local dialect explained or expanded upon.

Teatime in Taipei

“David, just enjoy your drink,” right?

Well, sure, in the case of both the tea ceremony and Tai-Pak, the rather superficial engagement with history is harmless enough. And yet, surface-level engagements with history can bring about their own set of problems, particularly when we talk about a symbol that is as ubiquitous as tea is in Taiwan.

A Taiwanese friend of mine recently mused to me that, in Taiwan, history education is basically synonymous with memorizing events, places, and dates. Since the end of martial law, history classes have certainly expanded their corpus of events, places, and dates, but curricula still largely avoid analysis of the ways that those events affected contemporaneous society, or their knock-on effects today.

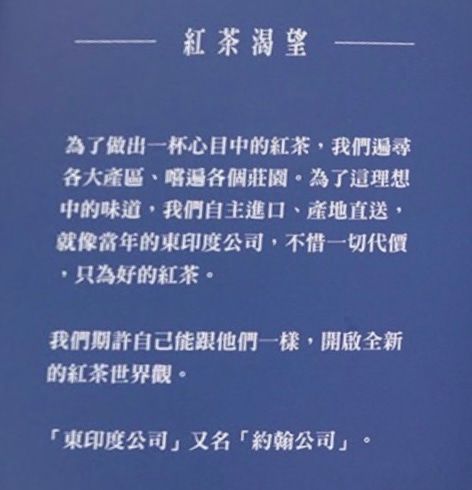

This “just the facts, ma’am” approach to history can be risky, even when we’re just talking tea. For example, the corporate story of a local tea shop (spotted by an eagle-eyed friend) praises the East India Company for “sparing no effort” to bring quality products to the world. The tea shop then goes on to say that they “aspire to be just like [the East India Company] … ‘The East India Company’ can also be called the ‘Yuehan Company.’”7

I might suggest that this tea shop has aspired too much. The East India Company may have been an “exporter” of fine goods, but the whole private-military-to-cement-colonial-domination-of-India thing, or the pesky detail of the company’s involvement in the Transatlantic slave trade, suggests that this is not a corporate model that we should be seeking to retrieve from the embalming chamber of history.

In other places, the stress on a “factual” view of history blurs boundaries between business, art, and life. This shows up in some places as surprising, but ultimately insignificant parallels, such as the fact that the tea-drinking silhouette on the Tai-Pak menu is the same as a product label used by a tea vendor in Taipei’s Xinyi district. In others, it completely blurs the boundaries between art and life, as when a news program (apparently) used an image from a La grande chaumière violette to stand in for a historical product.8

Where does all of this bring us? Well, in the case of tea, maybe nowhere. But in an age of MAGA, Trussonomics, Putinian historical revisionism, the rise of the far right in Italy (and much of the rest of Europe), or Chinese distortion of historical fact surrounding everything from Tibet and Xinjiang to Taiwan and the South China Sea, we would do well to turn our attention to the work that symbols do in organizing identity and acting as a focal point for political movements.

Something to think about over a cuppa, perhaps.

This is not to say these aren’t important. Scholars in a variety of fields have written about the importance of these kinds of symbols, from ethnomusicologist Thomas Turino’s Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), to sociologist Karen Cerulo’s Identity Designs: The Sights and Sounds of a Nation (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1995).

“Invented traditions” is a phrase coined by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger in their edited volume, The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983). It has remained a staple for scholars seeking to understand the ways in which nations cohere and evolve through time.

Though the festival certainly has historical roots amongst America’s colonizers, the modern incarnation as we know it didn’t really take shape until after the Civil War.

Emily Wilcox has written compellingly about this in Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019).

See, e.g., Turino’s “Nationalism and Latin American Music,” Latin American Music Review, vol. 24, no. 2 (Autumn-Winter 2003): 169-209.

Michael Herzfeld, Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics and the Real Life of States, Societies, and Institutions, 3rd ed. (New York, NY: Routledge, 2016).

In another tantalizing parallel, “Yuehan” is the Chinese name given to John Dodd.

It is possible that La grande chaumière violette used an actual historical design in their show, though none of the historical tea canisters I found online used this design. But whatever the weather, this particular tea canister is certainly the result of a promotion between the TV series and a local tea producer.