This week, I’m thrilled to have the chance to contribute a blog post for the 2022 Sinophone Musics Film Festival 華語音樂影響誌聯展! Many thanks to Professor Hsu Hsin-Wen 許馨文of National Taiwan Normal University for the invitation. This post is a little longer and a little more academic than usual (and it’s coming a day early to better fit the schedule of the festival), but it’s a subject I’m really excited about, so I hope you’ll still give it a read.

Well, I’m back at a film festival again. This time it’s the 2022 Sinophone Musics Film Festival 華語音樂影像誌聯展, an event featuring almost 20 ethnographic/documentary films about music. The festival’s screenings in Taipei and Hualian are coordinated by the Digital Archive Center for Music 音樂數位典藏中心 of National Taiwan Normal University 國立臺灣師範大學, while the films are jointly curated by research centers in Taipei and Shanghai. There’s a lot to love here, whether you’re a music scholar, a fan of documentary film, or just someone who likes music, so if you are in Taipei or Hualian over the next few days, do stop in to see some of these films!

Tickets are free! Check out the screening schedule here, and reserve your seats here! (Did I mention these events are free?!?)

About the Festival

The films featured in this festival all marry ethnographic fieldwork with documentary filmmaking, reflecting ethnomusicologists’ growing interest in multimedia presentations of their work. As you can see in the festival trailer below, the films cover subjects ranging from the “boat people” of Hong Kong, to the Chinese diaspora in Indonesia, migrant laborers in Taiwan (a topic I address briefly in a post from a few weeks ago), and aboriginal communities in China’s interior provinces and Taiwan. Taken as a body of work, these films give viewers a glimpse of the richness and diversity of Sinosphere musics. In its own words, the festival describes itself thus:

In response to the World Day for Audiovisual Heritage, the Digital Archive Center for Music, National Taiwan Normal University, and the He Luting Advanced Research Institute of Chinese Music and the Asia-Europe Music Research Centre of Shanghai Conservatory of Music jointly co-organized the 2022 Sinophone Musics Film Festival. Through film screening, dialogues with the directors and co-authors, and a series of discussions, we aim to invite music and film lovers and professionals to pay attention to the diverse sound cultures across Sinophone societies, the conditions in which they are situated, and the challenges they are facing. We hope you enjoy the events.

Writing from the standpoint of a researcher in the thick of archival research and fieldwork, watching these films gives me a welcome opportunity to take a step back and think about the nature of fieldwork, its ethics and obligations, its potentials and pitfalls. It has also been heartening to see how seemingly fragmentary snippets of film captured over the space of several years can coalesce into a moving, insightful narrative.

So with that, let’s jump in! I’m going to start by talking a little bit about three of the films I watched in advance of the festival, and then I’ll do a bit of hand-waving about how we might understand these films as speaking to, enriching, and complicating one another.

Ethnographic Film as Celebration

The first film I watched is a relatively short piece about Taiwanese composer Lai Deh-ho 賴德和, Music of My Home 吾鄉樂音 (dir. Tang Hsian-bin 唐賢賓). This is in many ways the most “musical” of the three films I viewed, in that large portions of the film focus on the Taipei Symphony Orchestra’s rehearsals and performances of Lai’s symphonic works. (There’s even a scene about correcting a misprinted note in the middle of a rehearsal!) This film is also a prime example of how a student director tackling a modest subject and working with an even more modest budget can produce a compelling documentary film.

Lai Deh-ho is an attractive subject for any young musician-documentarian in Taiwan. A fixture of Taiwan’s classical music scene since the 1990s, his large orchestral works are known for their complex fusion of local musical influences, including beiguan 北管, nanguan 南管, and aboriginal musics. According to his profile on the composers database for the National Culture and Arts Foundation 國家藝術基金會 of Taiwan, “Mr. Lai firmly believes that musical works should be rooted in the land and the people, which can also be understood as the national character. This belief explains his combining traditional Taiwanese culture and modern Western composition techniques in his compositions.” In short, Professor Lai’s oeuvre can be seen as an exploration of how to represent Taiwan’s unique musical, cultural, and historical circumstances in sound.

The film combines footage of rehearsals and performances with interviews with performers, conductors, and the composer. By juxtaposing Lai’s works and multiple performers’ perspectives on his music, this documentary helps us understand the differences between how composer and performers make sense of these often difficult works.

One of the major takeaways from this film is the keen awareness of local history here in Taiwan. Interspersed amongst rehearsals for the symphony “Mazu’s Bodygaurds” 海神家族, we learn how the composer’s musical imagination, plots from classic Taiwanese novels, and the composer’s own experiences of the White Terror all intertwine in this piece. By celebrating a single composer’s life and work, this short film reminds us that all art emerges against a backdrop of historical events. At the same time, this historical reality is always filtered through the lens of personal experience. What is more, this personal experience changes as it passes between composer, performer, and audience. Ultimately, although compositional intent is important, of equal importance is how we make sense of the works that we hear.

Ethnographic Film as Scrapbook

If the first film celebrates the life and work of one Taiwan’s most important living composers, the second film, White and Black 空白祭 (dir. Zhou Hongbo 周洪波), brings into focus the tragedy of barely-too-late ethnography.

The subject of the film is Chinese composer Wang Lisan 汪立三 (1933-2013) who at the tender age of 20 composed the piano piece Lan hua hua 兰花花, a work that turned him into a national phenomenon during the early years of the People’s Republic.

Wang’s fame rapidly turned to infamy, however, when in 1957 he and three classmates published an essay criticizing Xian Xinghai 冼星海 (1905-1945), the composer of the Yellow River Cantata 黄河大合唱, upon which now-canonical works like the Yellow River piano concerto are based. The essay’s timing couldn’t have been worse, coinciding as it did with China’s anti-rightist campaign. In the ensuing brouhaha, Wang and his classmates were branded “rightists,” shuttled for several years between labor camps and low-level regional cultural troupes. After the end of the Cultural Revolution—almost 20 years after his fateful article—Wang finally achieved some stability as a faculty member at the College of Music at Harbin Normal University 哈尔滨师范大学音乐学院.

So why do I call this a “barely-too-late ethnography”? Well, when this documentary began filming, Wang Lisan was still alive. However, he suffered from such advanced Alzheimer’s that he had become non-verbal. Thus, despite the fact that the film’s director was able to visit and interact with the composer at his home in Shanghai, the latter was no longer able to provide context or information.

In a sense, then, this documentary becomes a heavily editorialized scrapbook, piecing together interviews with the composer’s friends, classmates, and former colleagues, numerous diary entries, and recordings and performances of his work.

The picture that emerges from these ephemera is not a happy one. From youthful zeal for China’s socialist-era ideology, and belief in the nation’s meritocratic sloganeering, Wang’s later diary entries reveal an artist increasingly frustrated by lack of recognition and stymied by the bureaucratism of an academic institution that he felt to be beneath him. In interview after interview, his friends’ unwavering belief in his musical brilliance and personal generosity collides with descriptions of his alcohol abuse and political naïveté.

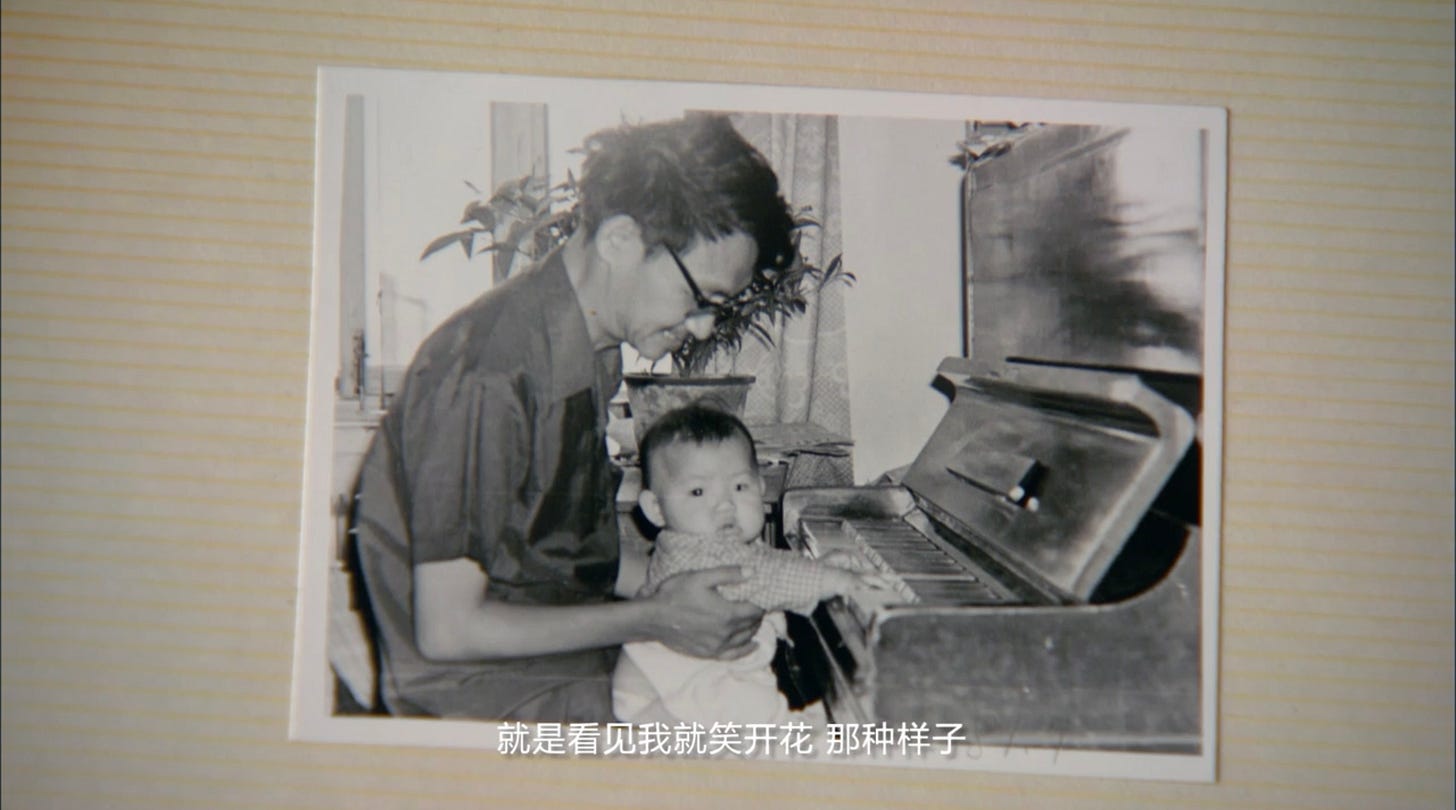

And yet, the film is also full of photos of the composer: a young man smiling as he composes at the piano; a middle-aged man smiling as he holds his infant daughter at the piano; a bespectacled, professorial man incongruously perched atop a playground rocking horse several sizes too small for him.

In our current age of social media confabulations of the ideal life, we should all know better than to trust a handful of cherry-picked photographs. But it is still difficult to reconcile the diarist whose dissatisfaction approaches despair with the smiling family man in the photos. The tragedy, then, of this barely-too-late documentary is that Wang Lisan is unable to provide further context, unable to give a retrospective opinion on the scrapbook gathered here. Physically still present, his mind has moved past the mundane world in which he lives, leaving his memories and narratives out of reach.

Ethnographic Film as Salvage

In 1983, James Clifford argued that the field of anthropology continued to labor under a “salvage paradigm,” one in which anthropologists saw it as their duty to preserve, guard or otherwise salvage cultures that were on the verge of being lost. The problems with this mindset are manifold, ranging from stereotypes of unchanging “primitive” cultures to academic delusions of grandeur couched in terms of salvation.1

Not that Clifford was the first to point out this problem. Ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl identified a similar problem in 1978, when he pointed out that the ethnomusicological tendency to venture out into the most isolated regions possible in search of “pure,” “untouched” musical cultures was a chimeric endeavor.2 But Clifford, with his usual literary flair, did manage to leverage the soundbite “salvage paradigm” to draw attention back to the problem of “salvage ethnography.”

In certain ways, Ballad On the Shore 岸上漁歌 (Ma Chi-Hang 馬智恆, 2017), takes part in this kind of salvage ethnography. Focusing in on the fishing communities of Hong Kong’s outer islands, this film consistently stresses the disappearing culture of Hong Kong's seafaring communities, and highlights the need for preservation. As such, the traditional songs of fishermen become a means to document a rapidly disappearing way of life—its musical culture, its language, and its community. So rapid is this decline that even the younger siblings of the film’s main interlocutor, the eighty-something Lai Lin Sau 黎連壽, reveal the surprise the felt the first time they saw their eldest sibling singing these songs on television. They explain that themselves are unable to sing the fishermen’s ballads because none of them speaks the language in which the songs are sung.3 Linguistic loss, coupled with economic pressures to move to Hong Kong proper, precipitates a massive loss of tradition amongst Hong Kong’s seafaring minority.

The salvage ethos of this film goes even further than its subject matter. You see, the film also documents the work of Kenneth Yip 葉賜光, an expert on fishermen’s songs. The camera follows Yip as he visits with his aging, ballad-singing interlocutors—a salvage within a salvage, if you will, preserving both the songs and the fieldwork that is preserving the songs.

Over and over, Mr. Yip meets with interlocutors who are mystified by his interest in these songs. “What’s the use of this? These songs serve no purpose” 有什麼用?這是沒用的東西, grumbles a certain Auntie Cheung at one point. The film’s director makes a similar point, musing in a rare moment of voice-over,

Knowing all of these grey-haired fishermen will eventually leave us someday, it dawned on me that something can never be preserved. When the fishermen’s ballads leave the life at sea, would people still understand them? … If we lack the life experiences of the boat people, only recalling the words and the melodies, it would be impossible to understand the emotions in the lyrics.

眼看一個個頭斑白的老漁民終有一天會離開,我明白有些東西是無法留下來的。漁歌離開了大海的生活,還會不會有人聽得懂? ⋯⋯如果我們缺乏水上人的生活經驗,單從文字與音符,根本不可能明白歌詞中表達的情感。

And yet, this final point is exactly where all three of these films allow us to see some of the ways in which ethnographic film potentially augments conventional ethnographic writing. While the two genres cannot substitute for one another, these two media—text and film—can help balance each other and make up for one another’s shortcomings.

Ethnographic Film as Something More

One of the thorniest methodological of ethnography as a mode of research (and one of its central theoretical critiques) is that, once the fieldwork is done, it has to be “written up.” Ethnography as process has to become ethnography as product. The act of ethnographic writing is, in some ways, an act of violence—it irrevocably changes the nature of the event from an irreplicable happening that unfolds in space and time, and converts it into a fixed, unchanging text. It also runs the risk of exoticizing or spectacularizing the very subjects we wish to hold up for greater understanding.

One way of dealing with this issue has been to lean into the genre’s weaknesses. Clifford Geertz famously called the process of ethnographic writing an act of fiction, “fictions, in the sense that they are ‘something made,’ ‘something fashioned’—the original meaning of fictiō—not that they are false.”4 This standpoint certainly draws attention to the creative impulse that underlies much of the best ethnographic writing, although it also opens up enough cans of worms to stock entire fishing fleets. For starters, if we subsume everything under the umbrella of “fiction,” where do we draw the boundaries between academic and literary enterprises?5

Even with Geertz’s embrace of “fiction,” however, one area where most academic writing continues to play a poor game is emotion. Don’t get me wrong—it’s in there, tucked in amongst the footnotes and the theory-dense prose. But you often have to look for it.6

In each of these three documentaries, the medium of film helps to bridge that emotional gap identified by the director of Ballad on the Shore. When the ethnographer Kenneth Yip breaks down in tears after hearing of the passing of one of his interlocutors, or when the camera is turned on director Ma Chi-Hang visiting the recently widowed fisherman Lai Lin Sau in his nursing home, it reminds us of the deep connections that develop between ethnographer and interlocutor over a period of many years. Wang Lisan’s daughter rescues White and Black from its more melodramatic tendencies when she rejects tragedy-porn narratives of her father’s life, saying, “Terrible though it may sound, three days before [my father’s death] he could walk around as he pleased. I’m sorry, that’s good quality of life!” 说不好听的,三天之前他可以来回溜达,I'm sorry,他这个生命质量已经很好了!And when Professor Lai tells the director of Music of My Home how his teachers were killed during Taiwan’s White Terror for trying to protect students from conscription, it reminds us that purely celebratory narratives are themselves fables, and that the full story is always more complicated.

This is not to say that documentary film solves all the problems of ethnography. Like written texts, film still fixes a unique event in time, turning it into an unchanging document. At the very least, however, film allows us to watch the event unfold through time (albeit through the mediation of the camera lens).

Then there are the ethical questions. If he had been in possession of his faculties, would Wang Lisan have consented to being presented on film in his reduced state? What are the ethics of drawing a salary based on the unremunerated musical labor of economically and educationally precarious individuals? What are the historical details that must be sacrificed to create a celebratory narrative, whether in film or in academic writing? While documentary film may not offer a resolution, it offers another perspective from which to think through these questions.

In Conclusion … Reserve Your Free Tickets!

If you’ve made it this far, dear reader, I applaud you. You are truly a glutton for punishment.

I’ve waffled about three of the films at this festival, but there is so much more to see—please visit the festival Facebook page, check out the schedule of events, and reserve seats for the many screenings and talks! And with my worries and my plaudits alike hovering over you like the specter at the feast, I hope you’ll have the opportunity to see some of these works, and think on the ways that these ethnographic films preserve, transmit, and rewrite our collective musical heritage.

James Clifford, “The Others: Beyond the ‘Salvage’ Paradigm,” Third Text, vol. 3, no. 6 (1989), https://doi.org/10.1080/09528828908576217. (Many thanks to my colleagues Cam, CJ, and Jenna, all of whom helped in my search for this article when my own institution’s e-resources failed me.)

Bruno Nettl, “Introduction,” Eight Urban Musical Cultures: Tradition and Change (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978).

To be honest, there’s a very complex politics of language at work here that is beyond my reach—I do not speak any Cantonese, let alone any of the Hong Kong minority languages that come into play in this film. In some places, the language of the boat peoples’ songs is identified as Hakka 客家, while in other places it is identified as Tanka 蜑家. For some, however, the term Tanka is falling out of favor, due to its past usage as a derogatory term for Hong Kong’s boat people.

In short, there are significant differences in the terms used by outsiders and by Hong Kong’s boat people themselves to identify their community, language, and songs, and both terminologies are undergoing rapid changes. For any readers who are more in the know than I am, I apologize for any errors above.

Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays (New York: Basic Books, 1973): 15.

This debate is long, heated, and ongoing. However, for a good distillation of some of its most basic contours, see Jeff Todd Titon, “Textual Analysis or Thick Description?” in The Cultural Study of Music: A Critical Introduction, eds. Martin Clayton, Trevor Herbert, and Richard Middleton (New York: Routledge, 2003): 171-180.

Here, I’m speaking in general. Works like Joshua Pilzer’s Hearts of Pine: Songs in the Lives of Three Korean Survivors of the Japanese “Comfort Women” (Cary: Oxford University Press, 2012), is proof that academic writing about music can retain emotional appeal for specialist and general reader alike.