Nostalgia for Today

"La grande chaumière violette," Historical Imaginaries, and Contemporary Identity

After a bit of half-baked theoretical faff, we started this discussion of nostalgia (and nostalgic nationalisms) with Light the Night 華燈初上, and a consideration of the ways that uncritical nostalgia for all things Japanese reflects certain tendencies in contemporary Taiwan, where media production is shaped partially by desire for a vision of Taiwanese identity that offers a more pluralistic vision of identity than the Han-centric narratives of the post-’49 KMT era. From there, we turned to A Touch of Green 一把青, and considered the ways in which a seemingly innocuous song set up pre-1949 China as an imagined object of desire and point of nostalgic longing.

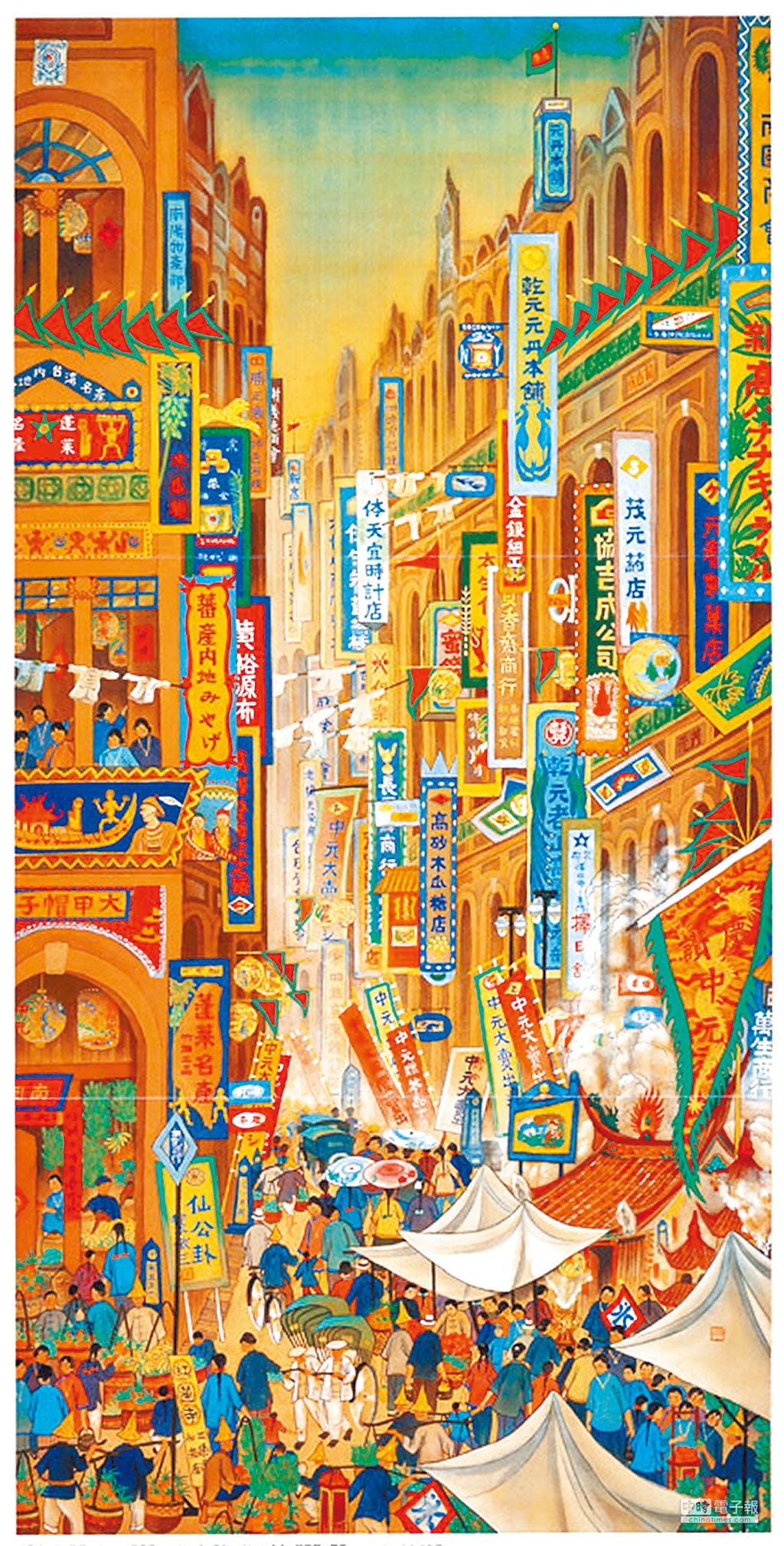

Today, we’re talking about one last series: La grande chaumière violette (Zise Dadaocheng 紫色大稻埕, literally Purple Dadaocheng). Dadaocheng 大稻埕 is a neighborhood on the waterfront in Taipei known today for the Instagram-ready, age-patinaed brick buildings left over from the period of Japanese rule. (Fun note: I photographed the colorful street sign that is the thumbnail image for this blog in Dadaocheng!) It was also a bustling port region that became hub for intellectual activity in early 20th-century Taiwan, and serves as the backdrop for most of this series about the nativist arts movement that emerged under Japanese colonial rule.

From Music as Object to Music as Subject

Often when we’re talking about music, we’re talking about music as an object, that is to say as a discreet piece or performance that can be analyzed in its own right. We can talk about Beyoncé’s Lemonade, the latest BTS song that dropped on YouTube, the revival (again) of the Zeffirelli production of Turandot, or the most recent tour of the Final Fantasy orchestra. We can talk about the vocal dynamism of the performers, the interaction of choreography and music, the length of the tenor’s final “vincerò” in “Nessun dorma,” or how moved (or overwhelmed, or confused, or bored) we were at being in the presence of a live performance.

Movies and TV shows can also take music as their object. Think Chicago, The Red Violin, or American Idol. Think Farewell My Concubine 霸王別姬, Woman Demon Human 人鬼情, or Youth 芳華. These are productions that are very much about the performance of music as a spectacle in and of itself.

But music can also serve as the subject of a movie or TV show. Think Amadeus, Diva, or To Live 活著. While each of these movies have scenes featuring musical performance, it’s rarely the focus of the movie—indeed, full scenes devoted to music are few and far between. Rather, the tensions and difficulties surrounding performers, composers, fans, and the social milieu in which music is made serve as a the launching point for the narrative of the film.

Sometimes, a film or show can take up music as both object and subject: Singin’ in the Rain and The Sound of Music not only center musical performance as a driving narrative force and structuring elements, but also interrogate the subject of music-making and its place in Western culture. Debbie Reynolds doesn’t just sing; when the curtain rises to reveal her singing (and turning her silent film predecessor into the butt of a cruel joke), it also shines a light on collective American assumptions about the nature of of prestige, talent, and musical merit. Maria doesn’t just sing about a few of her favorite things, the lyrics of songs like “Do, a deer” provide self-referential analogies that allow us to think through the nature of happiness, professional fulfillment, and good living.

Having and Eating Cake

In Light the Night and A Touch of Green, I talked about the link between music and nostalgia by thinking through music as an object of analysis in and of itself. But in La grande chaumière violette, although music and the arts serve as the entire raison d’être for the series, the series doesn’t actually provide much in the way of musical or theatrical performance.1 In this story, the main characters are two aspiring visual artists: Jiang Yi-An 江逸安, the scion of an influential tea-growing family, and Kuo Hsueh-Hu 郭雪湖, a fictionalized version of the early Taiwanese visual artist, and an aspiring spoken theater actress, Ru-Yue 如月. Filling various frenemy roles are figures such as the director of the spoken theater troupe, and a Peking opera actress from Shanghai who, for rather vague reasons, has decided to set up shop in Taiwan.

Narratively, the Japanese are the nominal antagonists of the downtrodden Taiwanese.2 Japanese police officers are shown getting in verbal arguments with characters known to favor Taiwanese independence, some secondary characters are thrown in jail for their convictions, and there are even several scenes in which (sparse) crowds of extras are seen protesting Japanese rule. Books are confiscated, representatives of the Japanese Governor General 總督府 exert pressure on prominent families, and the pressures of conformity to Japanese colonial ideals (discussed dolefully in Dadaocheng’s Japanese coffee houses) is routinely presented as a communal experience that cuts across Taiwanese social class. In this sense, La grande chaumière presents a comparatively clear-eyed view of the nature of Japanese colonial rule.

But if we take a peek at the arts as a subject of the series, a different picture emerges. Over and over, the visual artists portrayed in the series are shown to benefit from the instruction of Japanese teachers, and from the opportunities afforded by Japanese educational institutions. Crucially, this is not merely about the transfer of technical know-how. It is about the kindness and warmth of Japanese teachers towards Taiwanese colonial subjects, the support of the Japanese artistic class for their Taiwanese brethren. Even the main protagonist Hsueh-Hu 雪湖 benefits indirectly from the artists orbiting the imperial Japanese center of gravity, despite being unable to travel in person to Japan. In other words, this series portrays an emotional connection between Japanese and Taiwanese that contravenes the realities of colonial domination and suppression of local Taiwanese culture.

We can push this further. One of the main characters, after moving to the bustling hub of the eponymous Dadaocheng, the female protagonist Ru-Yue 如月 awakens to a desire to become a spoken theater actress. Although this desire takes shape in the context of a local theater troupe that advocates for Taiwanese identity and independence, there is also open acknowledgment that spoken theater osmoses its way into Taiwan’s burgeoning cultural scene via Japan.

And then there’s the frenemy of the the female protagonist, the aging Shanghainese Peking opera star Wan Hua 婉華 (played by real-life Peking opera star Huang Yu-Lin 黃宇琳), whose immaculate makeup can’t completely hide that she’s in the twilight years for the kinds of ingenue roles that made her famous, and whose occasional support for Ru-Yue is undercut by episodes of vicious sabotage. (It doesn’t help that both exhibit a romantic interest in the director of the spoken theater troupe.) Ultimately, about halfway through the series, Wan Hua concludes that there is no space for Peking opera in Taiwan. Bidding farewell to her fellow artists in Taiwan, she says, “There’s nothing worth staying for here. I’m from Shanghai. I should go back to Shanghai and keep acting there” (這裡沒什麼值得我留戀的。我是上海人。還是繼續回到上海演戲就好).

So here’s where we are: 1) some rather sparse protests against the Japanese colonial government; 2) the Japanese as the source of many of the most innovative and modern aspects of Taiwanese cultural life; 3) a Taiwanese cultural sphere in which there’s no space for the culture of Mainland China. This series manages (or at least tries) to have it all ways, rejection of Japanese imperialism and the influence of China, but an embrace of Japanese cultural patrimony. We can both have and eat our castella cake. In the context of a show that consistently shows scenes of agitation for Taiwanese independence, this easily slips into a metaphorical critique of KMT-era Mainland-centrism and its legacy.

What Happened to Nostalgia?

I’ve lost the tune, right? I promised a series of posts on nostalgia, and here I am on a rant about Peking opera, visual arts, and castella cake (highly recommended, fwiw). But here’s the thing. Everything I’ve described above is an exercise in nostalgia. The entire series is recounted as a flashback—indeed, the opening credits of the show feature rather dramatic aerial footage of the Golden Gate Bridge (yes, that Golden Gate Bridge) circa 1980.

How does the show end up in 1980s San Francisco, you might ask? Well, the economic background of the real-life Hsueh-Hu meant that, unlike many of his peers in the Taiwanese arts scene, he was never able to travel to Japan for study. That didn’t stop the KMT government from labeling his work as overly influenced by Japanese modernist techniques, leading him to flee the country in the 1960s, after which he ultimately settled in the Bay Area.

The premise for the telling of Hsueh-Hu’s story is that his friend Jiang Yi-An, the tea empire heir, has passed away. In sorting through his affairs, Yi-An’s son Xing-Xiong 幸雄, comes across a letter from his father to Hsueh-Hu, prompting Xing Xiong to travel to San Francisco in search of his father’s old friend. Thus, all of the events and relationships recounted above are all presented as an exercise in nostalgia. The vibrant hues, the improbable memories of the minutest conversational details, the emotional warmth and support that infused the arts community of Dadaocheng in the final decade of Japanese rule, are all literally presented as an extended trip down memory lane (a classic nostalgic device in the film-maker’s toolkit.) We are reminded of this fact by periodic trips back to 1980s San Francisco, with scenes of Hsueh-Hu and Xing-Xiong strolling together through the Grecian fantasy of San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts and the famed Golden Gate Bridge overlook.

These nostalgic devices are also used to enhance some of the emotional oomph of the series. Attachments to characters—their struggles, sufferings, and successes—easily slip into romanticized visions of the Dadaocheng of yesteryear. These romanticized notions are buttressed simple Googling, which instantly reveals a wealth of contemporary tourism materials for the district, which consistently invoke the social and economic vibrance of the exact era portrayed in the series. Facebook groups devoted to the district similarly celebrate the romance of Dadaocheng’s cultural organizations and crumbling colonial architecture.

Thus, we once again see a director playing the nostalgia card in a series that actively constructs a vision of Taiwanese identity.3 Furthermore, by framing the narrative with scenes of the artist’s life in San Francisco, the director indirectly critiques the KMT government whose persecution drove Hsueh-Hu away.

One. Last. Post. (No, Really … )

Alright. Last time I promised one last post. But here’s the thing, I’ve already gone on too long as it is, today. At the same time, because this blog is as much about collecting my thoughts as it is about sharing with you, dear reader, I think it’s worth having a brief wrap-up on nostalgia. So keep your eyes peeled tomorrow for a quick conclusion. I can’t promise that I’ll tie up all the loose ends, but I’ll at least try to hide them decently out of sight.

Other Posts in My Series on Nostalgia

This is a little different for the protagonist of the series, Kuo Hsueh-Hu 郭雪湖, a heavily fictionalized version of an important figure in Taiwanese art history. This character is often shown at work painting, and the series features cut-away shots of some of his most famous paintings in Taiwan’s National Museum. Nevertheless, these cut-aways function largely outside the narrative of the story.

If you’re curious, Wikipedia (predictably) provides a fairly thorough introduction to the history of Japanese domination of Taiwan.

This is not exactly hypothetical, in this case, as the works of the real-life version of the protagonist Hsueh-Hu are often presented in popular discussion as key documents in the formation of a distinct Taiwanese identity. See https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2021/11/02/2003767174.