Welcome back to another episode in which I hand-wave my way through some thoughts about nostalgia! We started last time with Light the Night and Netflix’s (presumably intentional) foray into 80s nostalgia with (presumably unintentional) undertones of Taiwanese national identity—a nationalist amuse bouche, if you will. Well, today we’re skipping the appetizer and heading straight into the main course. Today, we’re talking about A Touch of Green, a TV series set in the Chinese Civil War of the 1940s. And if by some miracle you’re still not nostalgiaed out by the end of today, come back one more time, for a discussion of La grande chaumière violette (Zise Dadaocheng 紫色大稻埕), an ode to the artistic and political foment of Taiwan under Japanese colonial rule.

This is a blog that is, in theory, mainly about music. With that in mind, the hit TV series A Touch of Green (Yi ba qing 一把青), produced by Taiwan’s Public Television Service (PTS), is a terrible show to write about, mainly because there isn’t a whole lot of music in it. The opening and closing themes are fairly boiler-plate pop tunes (albeit with rather grandiose orchestral introductions): the rather maudlin melody of the opening theme song is delivered by the inimitably breathy tones of Hebe Tien 田馥甄, while its closing theme counterpart is a moody barn-burner of a ballad performed by Yoga Lin 林宥嘉. Much like I suggested in my discussion of Light the Night, these resolutely contemporary songs that bookend each episode keep us from immersing ourselves in the era of the show.

What is more striking, however is the relative lack of music throughout much of the rest of the show. This is a series that takes you into the lives of three different couples living in the village for Republican-era China’s Air Force personnel and their dependents.1 The plot recounts in minute detail the characters’ petty jealousies, professional and personal challenges, and the massive stress placed upon the wives who are effectively held captive in the village while their husbands fly missions. And yet, for all the attention given to the mundane routines of cuisine, stitchery, scrapbooking, and mahjong, the village is a strangely silent place.

Oh, there’s plenty of music in the series, but it’s all for the benefit of the listener, relatively anodyne mood music that directs the viewer to the “correct” emotional response; it does not exist in the world of the show. It is music that happens outside the narrative and is thus inaudible to the characters.2

As a result, when music does enter the world of the characters, it is enormously striking.

Sounding Sepia with Zhou Xuan

In the 12th episode of A Touch of Green (about 1/3 of the way into the series), two of the three male protagonists have been jailed, while the third has been sent away on a mission, leaving all three of the female protagonists alone in the Air Force village. The mood is somber, and there is little conversation. Suddenly, Qian-yi, the wife of one of the jailed pilots, walks to a table to turn on the radio, bringing music into the world of the story for the first time. (Again, 1/3 of the series has passed at this point!)

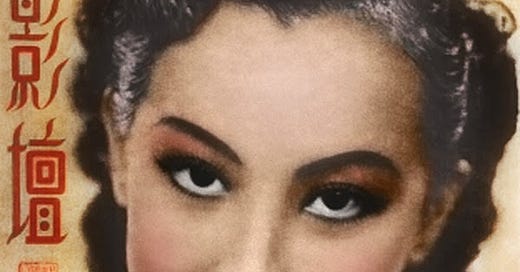

What emerges from the radio is the 1940s popular song “Xizi guniang” 西子姑娘. Historically, there’s good reason for the director to pick this song. First and foremost, it was originally commissioned by the Air Force as a recruitment song and remains known as one of the classic chestnuts of Chinese popular song—i.e., its presence in the Air Force village fits. But it is also heavily associated with the singer Zhou Xuan 周璇, the so-called “Golden Throat,” China’s first bona-fide megastar songstress.

Zhou Xuan’s voice remains distinct to this day. On the one hand, she produced a precisely focused, bright vocal timbre that was equally suited to the big-band standards of the day like “Shanghai Nights” (Ye Shanghai 夜上海) and folksier fare like the songs in her break-out film Street Angel (Malu tianshi 馬路天使). On the other hand, she had a shot-gun vibrato that flirted with cosmopolitan Snow White aesthetics. By picking a song intimately and famously linked to both the Republican-era Air Force and to an icon of Zhou Xuan’s stature, this song finally does what the opening and closing themes refuse to do: it places us in the sonic world of late 1940s China.3

But in the context of this scene, it is also a rather transparent gesture toward the nostalgic. Compared with much of the rest of the series, the lighting is exaggeratedly warm—incandescent bulbs on steroids. For once, there is little squabbling between the three women (who in spite/because of their close friendship certainly know how to push each other’s buttons.) And the act of turning on the radio is accompanied by an extreme closeup of the small, table-top transistor radio and the image of Qian-yi’s hands manipulating the machine’s analog dials—a hipstery analog idyll.

And then there’s the crackle in the early bars of the recording—the aural equivalent of a sepia filter on [photo app of your choice]. In an age of digital sound technology, the crackle and pop of mechanical arms and physical needles making contact with shellac are long gone, and noise reduction can eliminate the aural traces of the physical machinery used for the analog recordings of yesteryear.

So why the sentimentally sepia soundtrack here? For one, it turns the worried waiting of Air Force wives into something bittersweetly beautiful. The aural nostalgia reinforces the the nostalgia of the women on screen who flip through old photographs and clasp their lover’s bomber jackets. It also turns their daily ritual of mahjong into an event worth remembering. But most importantly, it marks a narrative turning point. Immediately before the radio scene, the youngest of the three female protagonists asks her friend, “Why do I feel like things are about to change?” (我怎麼覺得日子要變了?) What ensues, of course, is the Chinese Civil War, which ended with the victory of the Chinese Communist Party over the Kuomintang, and which set the conditions for the Gordian knot of contemporary cross-Straits politics.

Nostalgia for “Home”

This narrative turning point ultimately colors the entire subsequent series. From here, the various characters face severe mental health struggles, political persecution, sexual violence, life-and-death decisions about whether or not to engage in sex work, and death. Thus, the end effect is not simply an isolated scene that indulges in a bit of nostalgic reminiscence. It effectively turns the latter portion of the Republican era into a warmer, happier time, and sets it up as an object of desire, an imagined point of return, full of bittersweet remembrance.

Given that this is based on a short story written in the 1960s, this is perhaps not surprising. For many who fled to Taiwan at the end of the Civil War, reunification was seen as necessary and desirable outcome. And despite the fact that these so-called waishengren 外省人 made up a minority of Taiwan’s population, they controlled most of the levers of political power in the post-War decades, meaning that this desire for reunification was reflected in government rhetoric and policy.

But the way in which the nostalgia for pre-1949 China colors lurks subtly in the background of the latter half of the series stands as an interesting, if subtle, counterpoint to contemporary social movements that seek to establish a crowbar separation between Taiwanese and Mainland Chinese identity. Indeed, I have heard even Taiwanese friends that enjoyed watching the series question whether or not the same series could be made today, just a few years after A Touch of Green was filmed. But these doubts also give us a glimpse into the ways that the contest over Taiwan’s national imaginary is played out in the mass media, and the central role emotional appeals play in this contest.

One. Last. Post.

If you made it this far … wow, thank you! Next week, there is just one more instalment in my mini-series on music and nostalgia in contemporary Taiwanese mass media. We’ll be talking about the series La grande chaumière violette (Zise Dadaocheng 紫色大稻埕), and we’ll be thinking through what happens when music and the arts become a topic that we talk about, rather than art works that we admire on stage or on screen. We’ll be talking about humble visual artists, Peking opera star antagonists, and spoken theater ingenues. And as always, I’ll try to include plenty of fun photos!

Other Posts in My Series on Nostalgia

For those who may be less familiar with Chinese historical periods, the “Republican era” refers to the period after the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, and before the Chinese Communist Party’s victory in 1949. During this period, the Kuomintang 國民黨(KMT), also called the Nationalist Party, ruled China, nominally following principles of democratic governance. After 1949, the KMT fled to Taiwan, and for a period of several decades both the KMT government on Taiwan and the Chinese Communist Party claimed legitimacy for all of China.

We can refer to this music that happens outside the narrative as “extra-diegetic music.” This kind of music is key to almost all films—try to imagine Jaws without its famous theme, Psycho without the jagged violence of dissonant high strings, or Harry Potter spells without their glockenspiel accompaniment. These sounds are always for the benefit of the audience—surely if the characters in your average horror film could hear the tensely dissonant strings that accompany their entrance into an abandoned building, the characters would have the good sense to go wait out the storm at the nearest 24-hour convenience store.

The song is actually not performed by Zhou Xuan. But unlike the remake of “Yueliang daibiao wo de xin” in Light the Night, this arrangement closely mirrors Zhou Xuan’s famous recording and is clearly meant to evoke the earlier songstress.