The last several weeks have been a flurry of activity as I struggle to cram in as many research-related activities as possible before I head back into Chinese classes for a couple of months. Thus, it was a complete joy to attend two film-related events in the southern part of Taiwan a couple of weekends ago: first at the Chiayi International Art Doc Film Festival (CIADFF) 嘉義國際藝術紀錄影展, and then at one of the Music on the Lawn 草地音樂會 concerts at the Kaohsiung Spring Arts Festival 高雄春天藝術節 (KSAF).

The first of these events, the CIADFF, brings together avant-garde filmmakers and documentarians to explore the past and the present, both within the established domain of documentary film as well as in works that challenge our conceptions of what documentaries can do or even what counts as documentary film. At the same time, the CIADFF is explicitly committed to exploring the role of documentary film—and the arts more broadly—in a world that seems to be changing at an ever greater rate, and in the midst of ever more political, economic, and ecological turbulence.

The second event that I attended was a program at the KSAF entitled “Image · Sound Taiwan II” 影 · 響 台灣 II, accompanied by the byline “100 years, 100 films.” At this elaborate open-air event, held in the same cultural park as the Neiwei Arts Center 內惟藝術中心 about which I waxed poetic in my last post, orchestra and soloists accompanied a series of film montages that drew on movies ranging from the earliest days of Taiwan’s motion picture industry, to films released in cinemas earlier this year.

What particularly interests me here is the way these two events both stress history, and the way they use film, music, and film music as sites not only to celebrate history, but also to educate audience members about history. In the case of CIADFF, this approach to history is about incubating unorthodox or heterodox approaches to storytelling, and making space for new conceptions of the role of film and the arts in contemporary society. In contrast, the KSAF performance draws on almost the opposite approach: by partnering with the government-funded Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute and laying out a historical survey of Mandarin, Taiyu, and aboriginal films, this performance reinforces filmic orthodoxy by delineating a canon of Taiwanese film that points strongly towards conceptions of Taiwan as a distinct historical, cultural, and political entity that cannot be subsumed under a rubric of “Chineseness.”

So we have two events, the CIADFF: at which many of the films deal with the topic of history, and “Image · Sound Taiwan II,” in which films and their musics themselves become the object of history.

Despite their very real differences, both events showcase the ability of the arts—in this case, film—to establish, sustain, and contest historical narratives. Put differently, by selecting and curating a specific body of films, both events create a narrative arc that, even when not making direct claims on a (capital-letter) Historical Narrative, at the very least wink at history from across the room.

But the contrast between the two events also reminds us that every act of curation or canonization is exclusionary. By making decisions about what is in, both events by definition also decide what is out. Whether we’re discussion films about history or films as history, the in-versus-out necessity of programming, in which hard decisions about themes, compatibility between works, and run-times collide with the personal tastes and aesthetic priorities of curators and organizers, is the point of tension from which artistic claims to historical narrative emerge, and around which collective imaginaries of community and belonging coalesce.

History as Celebration (and Provocation):

Before I go on, it’s probably worth describing the overall context of the Chiayi International Art Doc Film Festival. Chiayi is a small city, ranked number 18 out of Taiwan’s top-tier administrative districts. With a population that tops out at around 260,000, it is a far cry from bustling metropolises like Kaohsiung or Taichung, much less the sprawling Taipei-Keelung-New Taipei conurbation.

Chiayi historically calls to mind two inter-related associations: first, it is the gateway to Taiwan’s Alishan 阿里山, the mountain region famed equally for its tea-growing prowess, its hiking, and its spectacular scenery; second, Chiayi is a historical hub of the lumber industry, the development of which enriched the coffers of Japan’s colonial government, even as it removed much of the old-growth hardwood from Taiwan’s mountain forests.

In establishing the CIADFF 10 years ago, the city also made a move into the experimental arts spaces that are often dominated by metropolitan hubs like Taipei and Kaohsiung. And yet, in the festival’s 10th anniversary opening ceremony, many of the speakers took pride in the audaciousness of the decision to base a film festival with international aspirations in a small city away from the traditional cultural centers of Taiwan. (I was able to attend this event thanks to the kind invitation of my friend Delphine Hsini Mei 梅心怡, a dancer, actress, and director whose short film Future Alice was featured in this year’s CIADFF. The same film won her the Best Actress award at the Cannes Shorts Film Festival—check it out, if it’s in your neighborhood, or email her if you want to include her film in a festival near you!)

The success of the CIADFF is evident in the group of people who assembled to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the festival. Naturally, the opening ceremony was attended by artistic director Huang Mingchuan 黃明川, a Chiayi native, documentary film maker, recipient of the 2021 Taiwan National Culture and Arts Foundation National Award for the Arts, and the driving force behind the CIADFF. Equally unsurprising, the guest list included local political stars like the mayor of Chiayi Huang Min-Hui 黃敏惠, along with the head of Chiayi’s Cultural Affairs Bureau Lu Yi-jun 盧怡君. But the festival’s international collaborations also attracted a group of foreign dignitaries who spoke at the opening ceremony, including Jakub Kopecký, Deputy Head of the Czech Economic and Cultural Office; Reto Renggli, the Director of the Trade Office of Swiss Industries in Taiwan; and Martín Torres, Head of Office of the Mexican Trade Services, Documentation and Cultural Office in Taiwan.1

From the mayor to the de facto ambassadors, each of the speakers in turn congratulated the CIADFF on reaching the 10-year milestone. On a level, this is the kind of semi-obligatory acknowledgment that is expected at any opening night gala, especially during a round-year anniversary. Taken in aggregate, though, the comments point to the festival as a site that accumulates its own history, and whose history over time has come to mesh with the history of Chiayi. Put differently, the repeated acknowledgments of the cultural cachet developed over the first decade of the CIADFF point to the ways that institutional histories can simultaneously highlight and shape the local histories of their host cities.

But history at the opening gala was not simply a celebration of accumulated time. Rather, festival director Huang Mingchuan also used the opening gala to gently provoke Taiwan’s cultural powerhouses. From the beginning of his speech, Huang noted that, ten years ago, most people encouraged him to take the easy road and establish his film festival in a place like Taipei. Later, skeptics of the CIADFF wondered why the festival didn’t feature more “mainstream” films.

This latter quibble elicited Huang’s most pointed critique of the evening. To Huang, contemporary film festivals around the world are plagued by a huge amount of programatic overlap. The result, for the CIADFF director, is that the major film festivals in Taiwan end up screening roughly 80% of the same content. Were the CIADFF simply to replicate these programming decisions, Huang warns that it would signal Chiayi’s willing consignment to second-class city status. In response to the skeptics, the careful cultivation and curation at the CIADFF show that it is possible to build a successful film festival that does not draw predominantly on the ever more homogenous corpus of internationally circulating film festival offerings.

So on the one hand, at the opening gala of the CIADFF, a decadal cycle of development and success represented a history to be celebrated. On the other hand, this same success—measured not only in the amount of time elapsed, but also in the extremely high proportion of world, Asian, and Taiwan premieres credited to the festival over the last decade—present an opportunity to strike back against both the mainstream wisdom of an increasingly commercialized world of cinematic arts, and also the institutional assumptions of the “major film festivals.”

History was not simply a topic of conversation at the opening gala of the CIADFF. Rather, it was a recurring theme throughout the festival, explored from a variety of angles in the films and round table discussions that took place throughout the opening weekend.

History as Inheritance

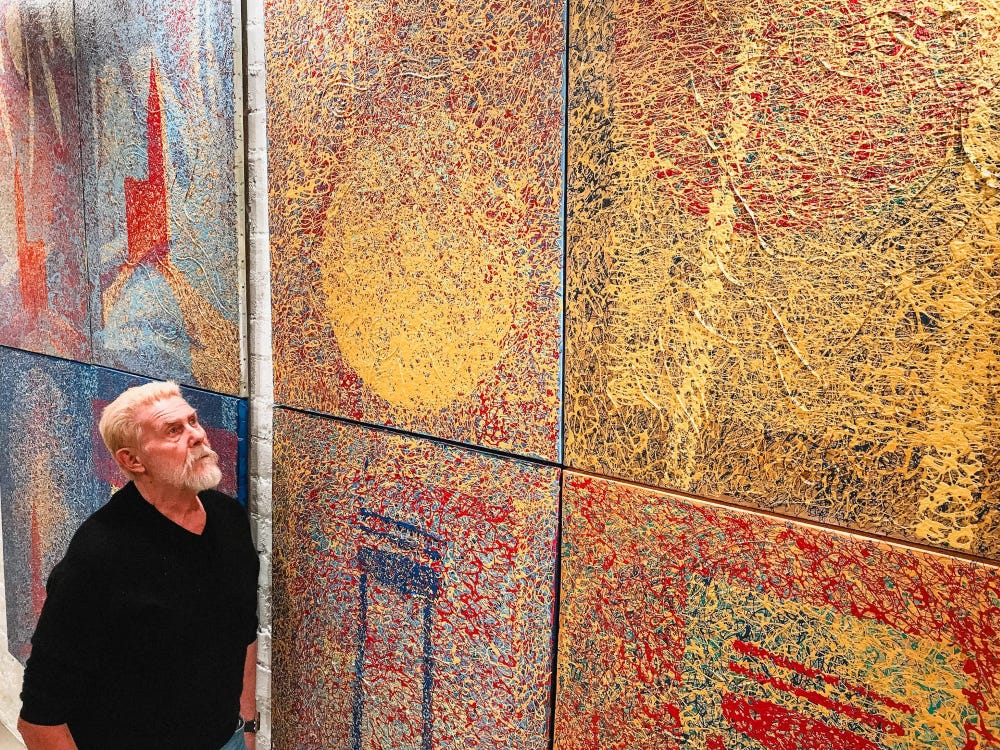

One of the featured films at this year’s CIADFF, Cri de l’âme, by Swiss filmmaker Dominique Othenin-Girard, follows the eccentric 76-year-old French-born artist Joseph Boehler as he prepares for his first exhibition in 10 years.

Boehler is (despite the astonishing dearth of Wikipedia documentation) a force in the contemporary arts world. According to the brief artist’s blurb on the website of Swiss public broadcaster RTS, his award credits include the jury prize at the Grand Prix de Peinture de Cannes and the “7 Collines de Rome” Prize. Thus, it may seem natural that he should be the subject of a major exhibition.

At the same time, Boehler sees himself as an artistic outsider: he was a boxer; he served in the military; he was raised in a broken home; he served time in a juvenile correction center for a horrific attack on his school teacher. And when the voice of Othenin-Girard asks Boehler from behind the camera if he is an artist, the painter immediately replies, “No.”

Despite his unusual background, this intimate, elegantly produced documentary shows us how Boehler also represents some of the most classic Western ideals of art. Art as laying bare of fundamental truths (“His work evokes the times he has lived through”); suffering as a necessary condition for art (“If you don’t feel any pain, you have no inspiration”); art as world-making endeavor (“What I liked to do was reinvent the planet”).

In the works and career of Boehler—at least as filtered through Othenin-Girard’s lens—the artist’s oeuvre becomes a record of history. The truth-making power of this record rests on the inheritance of centuries-old Western conceptions that regard art not merely as imitation of life, but as a revelation of deeper spiritual truths. In this sense, then, just as Boehler is shown to enjoy creating layered topographies on his canvases, the presentation of the artist’s works is composed of multiple layers of history. First there is the individual historical layer, which lays claim to revealing the artist’s true nature. Beneath that is a meta-historical layer, in which the truth-claiming power of the individual layer both relies on and reveals the Western philosophical substrate passed down through history.

Boehler does not come off as overly concerned with the economics of his art. Indeed, so loath is he to part with any of his paintings, after the artworks are taken to the display venue, he dons a blindfold so as to avoid looking at the newly denuded walls of his house.

In stark contrast, Boehler’s partner and manager Fanny is clearly absorbed by the potential for both economic gain and the consolidation of Joe’s legacy. Fanny is the driving force behind the exhibition, and a canny businesswoman who is keen to ensure that Joe’s paintings will become part of the artistic inheritance of Europe. Thus, Fanny’s presence adds to this film a layer that considers the future of history.

However, history permeated my weekend in Chiayi and Kaohsiung not simply as passive artistic inheritance. Other featured documentaries at the CIADFF appointed themselves record-keepers of history.

History as Record of Physical and Environmental Violence

Immediately following Dominique Othenin-Girard’s Cri de l’âme were two films that tackled violence from very different angles.

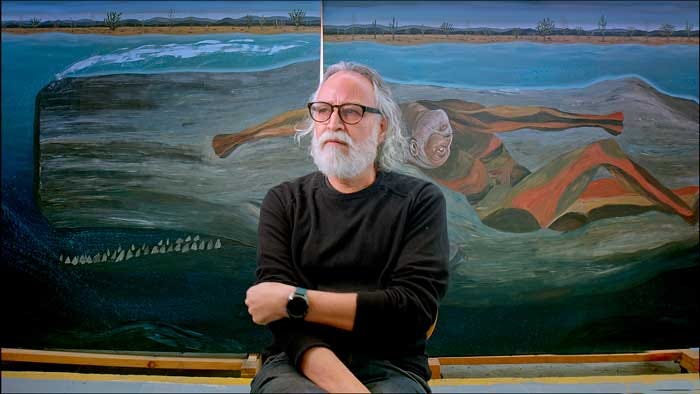

The first of these short documentaries, Gustavo Monroy: Art as Logbook of Vi💀lence, incorporates layers of violence in the most literal sense. First, there is the eponymous violence that is the subject of artist Gustavo Monroy’s paintings. To Monroy, recording this violence “is what being an artist is all about. In the end, you leave a record of the time you lived, good or bad, beautiful or dark, with lights and shadows.”

Critically, Monroy pursues this mission not as a source of titillation or as a way of downplaying the seriousness of the violence that has been an all-too-frequent fixture of Mexican society, but as a means “to exorcise the nightmare that we [in Mexico] have been living for many decades.” This violence, he makes clear, is often related to the cartels that continue to garner attention in the global press. But his earliest encounters with violence were at the hands of the sentinels along Mexico’s northern border, where as a teen Monroy encountered first-hand the violence caused by America’s border policies. In this sense, violence as one of the seemingly intractable problems of human history collides with the artist’s lived experience, both in the metropolis of Mexico City and in Mexico’s border regions.

The account of Monroy’s experience of violence is built upon director Darwin García’s experience of a different kind of violence, that of displacement. A Venezuelan citizen by birth, García left in 2017 to escape the social turmoil that continues to erode at the foundations of Venezuelan civil society. The director brings this perspective to his own work, which is based on the conviction that “art can serve as a powerful tool for social change and as a means to confront the realities of violence and injustice.”

When the camera is not pointed at Monroy himself during interviews, almost the entire visual content of the film is comprised of the artist’s works. This does not mean it is easy viewing, though. Art here is not an escape from real-life violence, but its enhancement: a reimagined Last Supper in which all of participants are decapitated heads; Adam and Eve wandering in the desert, stripped not only of their clothes, but of their skin as well; deserts littered with bones and corpses engulfed in flames.

The same phrase about art emerges in both both García’s and Othenin-Girard’s films—for Boehler’s champion Fanny, “his work evokes the time he has lived through;” for Monroy, as an artist, “you leave a record of the time you lived.” Despite this striking similarity of phrasing, however, García’s film is in many ways a counter-argument to Othenin-Girard’s profile of Joseph Boehler. Boehler’s life, buffered by Western European affluence and insulated from the mundane by the lingering after-effects of transcendentalist philosophies of the arts, unfolds in a rarefied artistic sphere that floats at a slight remove from the uglier realities of society. In painting, Boehler was able to disavow the violence that shaped his youth.

In García’s film, however, violence permeates art, even as art seeks to counteract violence. For Monroy, there simply isn’t enough distance between the artist’s workshop and the everyday fact of violence to eschew its presence in art.

In perhaps the most poignant remarks at the CIADFF’s opening ceremony, Mexican representative Martín Torres nodded towards art’s place not simply as an object of contemplation, but as a spur to public awareness and a call to international action. Although he acknowledged that these images are not always the source of tranquil contemplation that some art lovers may normally seek out, he also made clear that Mexico was proud to welcome immigrants like García, who are able to draw global attention to problems that are not purely of Mexico’s making, but that also reflect the complex political and social legacies of colonization, war, and racialization that continue to influence North America’s international relations today.

If Gustavo Monroy: Art as Logbook of Vi💀lence is an elegantly produced, introspective film, the film that was programmed alongside it, Chinese performance artist Nut Brother’s Song of the Silenced 情况有点复杂 (literally, “The Situation Is a Bit Complicated”) is an unabashedly slapdash affair. It’s a film comprised of grainy cellphone footage, bad camera angles, and unbalanced sound.

Nevertheless, this film tells the story of Nut Brother’s attempt to use a heavy metal tour to bring attention to devastating environmental and health consequences of toxic heavy metals leaching into China’s soil and ground water.

In many ways, the film is a record of failure. First, Nut Brother struggles to book acts who will participate in the events. Then, after the tour’s first stop, local authorities shut down most of the remaining performances before they can begin, usually under the guise of the tour “lacking proper permits,” or for reasons of COVID-19 health restrictions.

Nevertheless, in a remarkable turn of events, Nut Brother and his colleagues convince local authorities at one stop to “review their lyrics” (a requirement for permitting) in their hotel room. What ensues is a bed-top performance, caught on multiple smartphones, for authorities whose rejection of the tour’s “application” is a foregone conclusion.

In some ways, the most remarkable feature of Nut Brother’s film is its very existence. To film and produce this clearly presents a significant personal risk for many of the (completely unmasked) tour participants. To then successfully export the film to international film festivals is yet another feat in the face of the PRC’s often overwhelming state surveillance and control of online activity.

Nut Brother’s rather fearless (though frequently despondent) confrontations with authorities also serve as a reminder of what risks artists assume when they choose to speak truth to power. For readers living in democratic nations, it is easy enough to critique artists who “sell out” and play along with state power. This is fair enough for the Anna Netrebkos or Valery Gervievs of the world, whose multimillion-dollar careers could easily continue apace if they chose to speak out against war criminals of a homophobic, racist or otherwise authoritarian bent.

But for the average working artist who, at the best of times, lives in economic precarity, Nut Brother’s plight illuminates the very real risks that emerge from this kind of activism, both in the economic terms of an artist unable to perform and in the political terms of a subject of intense state scrutiny. As such, Nut Brother’s confrontation with petty local authorities not only reveals China’s bureaucratically inertial surveillance regimes. The work of this performance artist also forces uncomfortable questions about what aid and activism viewers in liberal democracies are willing to bring to bear when artists actually live up to foreign audiences’ demands for speaking truth to power.

History as Identity

Thus far, I’ve talked mainly about the way that the documentaries at the CIADFF chronicled history on a grand scale: Western aesthetic philosophies, deep-rooted social histories of violence, and the violence of the state against its own citizens, both through active suppression of its own citizens, and through passive tolerance of industrial depredations.

History does not just happen on the scale of the nation, however. It also happens at the level of the individual. This idea of history on the most granular of levels was the focus of a screening that brought together three theater companies, first for a short documentary screening, and then for a round-table discussion with each of the company directors. And to me, this is where things get really interesting because, in discussing how history influences their creative endeavors, we also gain a glimpse of the ways that artists first narrativize history, and then weave these personal experiences of history into their work.

The three companies in question are Assignment Theatre 差事劇團, Golden Bough Theater 金枝演社, and Our Theatre 阮劇團. Although there are significant differences between the companies, each represents a different moment in the development of Taiwan’s rip-roaring grassroots theater scene.

The film segments produced by these companies were not documentaries in any traditional sense of the word. Truth to be told, taken individually, the compilation of archival footage that each company stitched together to give an overview of their activities might simply be taken for an extended advertisement. Taken together, however, these presented a concise record of the ways in which Taiwan’s theater scene continues to grasp towards story-telling media that can adequately represent the full complexity of the island’s diverse political, social, and cultural history.

Seeing as the documentary could only offer snippets of the troupes’ work, however, what struck me as more illuminating was the way in which each individual director narrated their own personal history into their work. In the case of Assignment Theatre’s Chung Chiao 鍾喬, a recurring theme in his productions is the use of a leftist perspective to empower “normal people” (i.e., not necessarily trained actors) to tell stories that were suppressed during the decades of the White Terror. This distinctly activist approach, which helped establish Taiwan’s experimental leftist theater movement, was built on Chung’s own experiences as an activist and artist participating in the global leftist movement during the 1970s, particularly in Latin America. Here, Chung’s personal experiences tie together his work and his connections to the global leftist movement, consistently striving to bring a global history of leftist arts to a Taiwanese theater community and viewing public that previously had no way to access these traditions.

For Wang Rong-Yu 王榮裕, the founder of Golden Bough Theater who is about 5 years younger than Chung Chiao, the history he draws upon for inspiration is even more personal. Wang Rong-Yu started his career as a highly successful computer engineer in some of the headiest days of expansion in Taiwan’s tech industry. However, he eventually left his code monkey position to found Golden Bough.

One of the primary motivators that the director pointed to during the round table was the fact that he grew up in an operatic family—a proud native speaker of Taiyu, his parents were performers of gezaixi 歌仔戲, Taiwan’s native form of Chinese opera. As he looked out at the cultural landscape of the late 80s and early 90s, Wang Rong-Yu found it strange that all of Taiwan’s cultural production was in Mandarin, and that local languages were almost completely unrepresented. At the same time, by dint of his rather cosmopolitan education and professional experiences, he was also an admirer of both musical theater and Greek tragedy (as seen in the video above).

As Wang Rong-yu tells it, he eventually realized that these two chronologically disparate genres from the West share many structural elements with the gezaixi that he grew up listening to. Ultimately, he founded Golden Bough as a way of revitalizing Taiwanese theater, attracting new audiences, and connecting Taiwanese audiences to the world through stories that share common themes with Taiwan’s own history of political repression and territorial disputes. In this sense, personal history provides a creative impulse for creating new kinds of theatrical expression for a distinctly modern, culturally hybrid Taiwan.

But Wang Rong-Yu’s experience is also is formed by the historical reality of having grown up in an age where the mainstreaming of Taiyu theater and local Taiwanese culture still faced significant political proscription. In contrast to Chung Chiao, who worked in the arts and theater from an early age, and who therefore entered the industry at a time when Mandarin was still the dominant linguistic force in the Taiwanese arts, Wang’s later entrance on the theater scene due to his time in tech meant that the potential of a mainstream Taiyu theater was no longer completely foreclosed upon.2 Thus, histories of politics, family, and education all align just so to facilitate the emergence of Golden Bough’s uniquely syncretic form of Taiyu theater.

Finally, Wang Jhao-Cian 汪兆謙, the young founder of Our Theater 阮劇團, spoke about his experience as a member of the generation whose childhood straddled the final years of martial law and the lifting of martial law.

For the younger Wang, elementary school memories of martial law combine with a confidence in Taiwan’s democratization, freeing him to experiment with both form and geography. Where previous generations of activist directors may have felt the need to emphasize Taiwan above all else, Our Theater has explored regional solidarities through bilingual productions, as in their 2022 production of a Taiyu-Cantonese musical co-produced with a Hong Kongese theater company.

Similarly, where previous generations gravitated toward the political center of Taipei, or the industrial hubs of Kaohsiung and Keelung, Wang Jhao-Cian felt empowered to found his experimental theater company in his hometown of Chiayi. In a similar way to the CIADFF itself, Wang’s decision to base his company outside the metropolitan center also opened possibilities of broadening conceptions of feasible geographies for Taiwan’s theatrical community.

For each of these directors, the types of performances that were feasible were conditioned by the historical realities of the rapid political and social change that characterized a Taiwan in transition to democracy. At the same time, the talks of each of these directors makes it clear that history is not an abstract concept to be transmitted to passive audience members in search of entertainment. Rather, it is a lived experience that shapes their creative processes and goals. By anchoring their work in these lived experiences, they also seem to invite their audience members to make their own personal connections with the local, national, and regional histories of Taiwan.

History as Nation

Finally, returning briefly to the metropolis of Kaohsiung before boarding the train back to Taipei, my weekend ended with a very different kind of history. This was an outdoor concert at the Kaohsiung Spring Arts Festival, featuring a bevy of nationally popular vocal soloists (including the same Lin Shengxiang 林生祥 who appeared in my last post about the Gongsheng Music Festival), and anchored by the Kaohsiung Symphony Orchestra 高雄市交響樂團.

The title of the concert, “Image · Sound Taiwan II” 影 · 響 台灣 II requires a bit of explanation as it is a play on words. But to my nationalism-fevered mind, it’s worth spending time on these linguistic details, because it offers a glimpse of the attitudes that anchor this program.

In Chinese, ying 影 (lit. “shadow”) is part of the word for movie (dianying 電影 or yingpian 影片); the word xiang 響 relates to sound and music (as in the name of this concert’s performing ensemble, the Kaohsiung Symphony Orchestra, in Chinese the Kaohsiung jiaoxiang yuetuan 交響樂團). If we stick these two characters together, however, we come up with the word yingxiang 影響, which means “to influence,” or “to impact.”

Thus, this title operates on two levels simultaneously. First, it nods to the building blocks of the program, that is, images and music. In this reading, we can read the title of this concert as something along the lines of “Image · Sound Taiwan.” But on an ideologically more interesting level, the performance title also lays claim to the influence of the past hundred years of Taiwanese cinema and music on Taiwanese identity. In this second reading, we can see the concert title as something along the lines of “Impact Taiwan.”3

As it happens, there was a bit of false advertising at this concert. This was not, as the byline suggested, “100 years, 100 movies.” In fact, it was “100 years, 103 movies,” along with over 50 of Taiwan’s most iconic film scores. These were stitched together in a series of thematically discreet montages, drawn from across the spectrum of Taiwan’s Mandarin, Taiyu, aboriginal, and Hakka films. The source materials ranged from Taiwan’s earliest black and white films to films released earlier this year, and the program’s themes covered everything from stirring sports stories to queer romance, from contemporary jump-scare horror to animated children’s classics.

If this sounds like a lot, well, it was. That said, this was a wildly popular event with strong attendance—I arrived only (only!) an hour before the downbeat, and already the entire middle section of the lawn was fully occupied by people who had come equipped with lawn blankets, pizza boxes, and beer koozies.

Once the concert started, the carefully plotted themes made it an eminently enjoyable and often moving concert; the orchestral playing remained perfectly synced with the images without ever giving an impression of rigidity; and the charisma and charm brought by the parade of vocal soloists generated enough variation in pace, timbre, language, and genre to keep the concert feeling fresh, even as the concert approached the three-hour mark.

Entertainment value aside, there was also a distinctly pedagogical flavor to much of the evening. In the program book, introductory comments from Kaohsiung’s mayor proclaim that events like this “once again bring artists from around the world to Kaohsiung, and through the arts allow the world to experience Kaohsiung [and] understand Taiwan.”4 Kaohsiung’s Cultural Department director explains, “This year’s [concert] will guide audiences in a review of Taiwan’s variety of musical styles over the last 100 years.”5 And the representative from the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute tasked with putting the whole program together consistently references both the 100 years of Taiwanese film history covered in the concert, as well as the many experts and performers who came together to make the performance possible.

Even in a long concert such as this one, however, hard decisions have to be made about programming (indeed, the almost-three-hour run time greatly exceeded the advertised two hours.) The TFAI representative acknowledged this directly in his program notes: “Over the past century, there are definitely more than 100 films that have captured our hearts and minds,” before immediately going on to emphasize, “but we have carefully selected the most essential scenes from 100 movies.”6

Elsewhere, the concert’s educational impulse became even more apparent. For example, both before the concert and during intermission, audience members were cajoled with promises of free swag into participating in a quiz testing their knowledge of Taiwanese film. For me, this quiz was like catnip, because this is where the core choices about what constitutes a Taiwanese film worthy of being universally recognized really came to the fore.

For example, one of the warmup questions asked audience member to recite Tony Leung’s only spoken line in City of Sadness 悲情城市 (which film I just can’t seem to get away from.) Even the first time the quiz host asked the question, I was surprised by the number of people who were able to loudly shout, “I am Taiwanese” 我是台灣人!7 By the third time the moderator complained, “I can’t hear you,” the almost everyone within earshot yelled, “I am Taiwanese.” Elsewhere, the MC reminded audience members that all of the movies were listed in the program, and encouraged everyone to go home and re/watch those films with which they were less familiar. In effect, the audience who had just roared “I am Taiwanese” was given a kind of nationalist homework assignment.

But elsewhere, I was reminded of the ways in which institutions like the TFAI control the narratives of what counts as acceptable iconicity. This was particularly striking in another one of the warm-up questions, when audience members were asked to identify the movie this picture comes from:

Now, the film in question, Beyond Beauty: Taiwan from Above 看見台灣 is in many ways a rightfully famous documentary, full of stunning aerial footage of the island’s natural beauty, as well as the environmental toll of a weak and/or poorly enforced industrial regulatory environment. But the final scene of the film, its emotional climax, is a group of aboriginal children, literally perched atop a mountain, singing in their aboriginal language and dancing for the camera before lofting Taiwanese flags into the air and waving them.

Ugh, David, you killjoy. What’s the big deal?

Well, the problem is that Taiwan’s aboriginal peoples, like indigenous communities the world over, have long been an object of primordialist fantasies, pictured as happy, childlike, peoples who sing and dance their way through their natural forest surroundings. In short, these narratives often dehumanize indigenous peoples, relegating them to an eternal state that is adjacent to, but not quite part of our modern world.

The problem here, however, is not just the fact that the final scene of this film recycles well-worn tropes about Taiwanese aborigines. The problem is amplified by the fact that, as the only aboriginal scene that is singled out for use in the “must-know” Taiwanese movie quiz, powerful organizations like the TFAI put their cultural and academic weight behind these harmful stereotypes.

This points us toward the power of institutions to reinforce narratives. By deciding that a film like Taiwan from Above is more deserving of iconic status than a film like the Golden Horse Award-winning Gaga 哈勇家, which offers a grittier look at contemporary aboriginal life, the TFAI also implicitly wields its institutional clout to define the “right kind” of aboriginal Taiwanese subject. And that in turn is the image that gains preeminence in the artistic-historical narrative that emerges from the programmatic fabric quilted from the scenes and cels of the last 100 years of Taiwanese cinema.

The Conundrum of the Arts and/as History

On the one hand, the arts are intricately linked with the kinds of histories from which it is possible to build social, national, and political identities. In cinema of one’s own nation, we often find the quintessential images of “home,” stories that resonate with our own lives, and musics that both sound like “our music” and intensify the emotional impact of image and narrative. When multimedia genres like film are deployed cleverly, they can create a feeling of connection to events, people, and times that might otherwise seem only distantly related to our own lives. In this sense, certain advantages accrue to both documentary and narrative films that are used as vehicles for historical narratives, particularly those that aspire to cultivate emotional associations with the nation.

Film, theater, the visual arts, and music also operate on different historical levels, from the global to the deeply personal. Nevertheless, as we see in works as varied as Darwin García’s Gustavo Monroy, Nut Brother’s Song of the Silenced, and the collaboration between Assignment Theater, Golden Bough Theater, and Our Theater, these historical perspectives are frequently filtered through the lens of the nation—whether it’s Monroy’s desire to turn his work into a “logbook” of the violence that gnaws at Mexican society, or Wang Rong-Yu of Golden Bough Theater, who observed that one of the most important influences on his work, his Taiyu opera star mother, was also a “national treasure.”

But films themselves are limited in their narrative scope—a single work can only present so much of the picture, and many directors will understandably make artistic concessions to make their stories more accessible to audiences. As such, no matter how deeply researched or considerately constructed, “artified” historical narratives that gain traction with the public frequently provide only a fragmentary view of the complex whole.

And then there is the issue of the artistic histories that emerge when certain repertories or corpuses crystallize into canons. This process is by definition one of valuation, hierarchization, and exclusion. To a certain extent, this is based on audience response, a sort of reception habitus that turns certain works into canonized classics, no matter what the studio’s ledger sheets report (can anyone say The Wizard of Oz or Fantasia?)

Mass acclaim aside, however, public opinion can be greatly shaped by institutions. While I have more faith in the viewing public than Adorno—I do not believe, for example, that “to like [a piece of popular music] is almost the same thing as to recognize it”8—I do acknowledge that repetition, particularly when backed up by the authority of experts, can heavily influence public perception of a work’s value.

Thus, when institutions like the TFAI elevate singing aboriginal children perched atop a mountain and at one with nature as the most classic image of Taiwanese indigeneity, they exert pressure on public perception of what Taiwan’s aboriginal peoples can and should be. This is particularly true for members of the Han majority who only rarely have contact with Taiwan’s aboriginal communities.

At the same time, when organizations like the CIADFF choose consciously to work against the cultural norms established by mainstream film festivals and organizations like the TFAI, the vision of filmic and/or national history they present is also shaped by those institutionally constructed histories, if only by virtue of operating in the spaces as yet unoccupied by those more established, more powerful organizations.

So what’s the answer? Certainly, we can’t say that we’ll just stop elevating certain films, musical pieces, or artworks to the status of “classics.” This process of elevation is, from what I can see, a somewhat natural response to certain artworks. Nor do I think it is wholly negative when we leverage our artistic histories to explore histories of nation.

But we can raise awareness that these stories are incomplete. We can encourage audiences to explore on their own. We can provide resources to connect audiences with different media: novels, news reporting, memoires, writings by experts (both from within and outside academia) geared toward general readerships. And while not everyone will take advantage of these resources—life is busy, and we’re routinely being told that social media is rapidly reducing our collective attention span to that of an amnesiac goldfish—it at least drives home the point that these works do not tell the whole story.

And it even reminds our audiences that, no matter how deserving the organization or how brilliant past productions have been, the institutional prestige that lends weight to the performances and histories that we witness is itself highly contingent, shaped by the combined forces of social discourse, capital, and downright luck. Of course, then we have to ask, how many organizations are willing to remind their audiences of these facts?

Due to Taiwan’s unique diplomatic status, these representative offices are the names of the diplomatic missions that represent their nations and that provide consular services to citizens living in Taiwan.

Later, Chung Chiao did in fact work with theater companies that use Hakka, another of Taiwan’s Sinitic languages that faced significant legal and political discrimination during the period of martial law. However, he Chung agreed when Wang Rong-Yu characterized his work as primarily Mandarin.

As for the Roman-numeral II in the title, I was initially disappointed that I had missed “Image · Sound Taiwan I.” Once at the concert, however, I learned that “part I” of this concert occurred in 2016, a fact that (slightly) helped to tamp down my FOMO.

2023 年底十四年「高雄春天藝術節」“讓世界透過藝術感受高雄、瞭解台灣 …… ”

“今年《影 · 響 台灣 II》節目 …… 携手譽有電影的美麗聲與影呈現在大家面前”。

“百年歲月下讓我們魂牽夢縈的絕對不只 100 部電影,但是我們精挑細選了 100 部電影精華”。

More accurately, Wenqing’s line is “I … Taiwanese” 我 …… 台灣人, but given the casual setting of the quiz, I’ll allow it.

Theodor Adorno, “On the Fetish Character in Music and Regression of Listening,” in Essays on Music, ed. Richard Leppert, trans. Susan H. Gillespie (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002): 288.