Before beginning, I should say that there is some colorful language in this post. However, as it is impossible to talk about these works without using the artists’ own language, I will not (nor do I want to) alter their language in any way. If strong language makes you uncomfortable, please tune back in next week!

A couple of months ago, I went to the opening of a small, independent art show called “Never Forget Your Name!” 咪唔記得你個名啊. The show featured the works of three Hong Kongese artists, all of whom have been forced to leave Hong Kong due to the territory’s ever more precarious political situation. In at least two cases, these artists’ works directly contributed to the circumstances leading to their emigration.

The three artists, whom I will refer to by their respective social media profile names (for reasons that should be self-apparent), each brought strikingly different visual sensibilities to their work. But each of the works on display at “Never Forget Your Name!” directly addresses Hong Kong’s political fate over the past few years, giving us a glimpse of both the role of art in politically precarious times, and the incredible personal sacrifices undertaken by the artists who connect their work with their activism. In their own words, the artists state,

And so it is, we have landed in Taiwan, a reminder to ourselves at the time of being dazed and confused, “Not to forget your name … Indeed, NEVER forget your name!” …

How we are being addressed relates to the place we are in and our identities. We, Hong Kongers, have been battling difficulties in every way. It has also altered our “names,” and made use unsure of ourselves … To the three of us, ART is the way not to forget our names. …

At the end of the day, as we have migrated to Taiwan, when we are dazed and confused, we will never forget our names. So call us by our names.

I will confess that I have debated whether or not I am even qualified to write this post. I am not a trained artist. I am not a political exile. I am not particularly familiar with Hong Kong. There is no music to speak of in this exhibit.

And yet, this small, independently produced art show, and the community that came together to produce and support it, was also deeply moving to me. Ultimately, I decided that sharing the work of these three artists was more important than my own uncertainties about my qualifications. For any mistakes in what follow, I simply beg understanding in advance.

Missy Hyper: A Riot of Color

Missy Hyper 茜利妹 was one of the first artists I met in Taipei, in a seminar at my host institution. Missy Hyper is a prolific multimedia artist, with shows of her physical media throughout Asia and the United States, as well as an active pipeline of digital media (much of which is in English, for any who might want to browse her Facebook page).

Thus, when she told me about this show, I was excited to have the opportunity to go and see her work in person. I had been in Hualien for a couple of days for research, and made my way from the train station straight to venue, Hó-Sńg House 河神的丸子, a coffee shop/arthouse/exhibition and performance space in Taipei’s Da’an District 大安區. (Fun fact: the venue’s name is a tribute to Studio Ghibli’s Spirited Away, referencing the medicine given to Sen, the movie’s protagonist, as a reward for helping a river god.)

Hó-Sńg is in one of those old Taipei buildings that is nestled discretely behind an ornamental metal gate, with a lush garden courtyard between the store and the building’s alley-front entrance. The main floor of the space is a café and shop selling everything from tote bags and coffee table books to coasters and the works of local artists. The building is long and narrow, with a clattery staircase at the back of the space leading upstairs to the exhibition and performance area.

As I entered the shopfront, Missy Hyper’s head popped below the second landing. Spotting me, she immediately ushered me upstairs, and spent a generous amount of time introducing me to both her works and to the exhibition’s other two artists.

Missy Hyper’s name is fitting. She is a bundle of energy and enthusiasm, talking me through her works with a combination of intensity and humor that prevented her presentation from slipping into self-earnestness, and tackling serious subjects with a quip and a laugh.

The first thing I was struck by in Missy Hyper’s works was the color. Her bright acrylics virtually explode off the mottled walls of the exhibition space. She initially introduced me to her series, “In Da Mood 4 HK (Series 2)” 香港心情. Now, my Chinese is fairly good in most situations, but my command of the language lexically drab, at best, if not downright prudish. Thus, I was not immediately struck by the fact that this series of paintings is dedicated to Cantonese swear words, translated in the artist’s statement as, “Fuck, Dick, Dick again, more Dick, Cunt” 𨳒 𨳊 閪 𨶙 𨳍.

When I asked about the inspiration for the work, Missy Hyper explained to me that, in 2020, she presented a talk show series, a continuation of a show that she toured internationally in Australia, Europe, and Asia starting in 2018. Four performances of the show in Hong Kong were later uploaded to her YouTube channel, where you can still watch excerpts.1 In the show, she satirized everything from Donald Trump’s flagrant disregard of the lived experience of Hong Kongers under increasingly draconian Chinese state crackdowns, to the emptiness of Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s political rhetoric. Enraged by years of political protests that not only went unheeded, but led to ever harsher repression by the state, the online talk show became an opportunity not only to continue her previous shows, but also to vent spleen.

The original series of paintings was composed as a raffle prize for the talk show. At the end of each taping, numbers were drawn from a box, and a lucky audience member walked home with Missy Hyper’s somewhat potty-mouthed artwork. (In one episode, just before Missy Hyper read out the winning number, an audience member shouted that he wanted the painting. Although his bargaining failed to sway the method of selection, fate seems to have been on his side—upon reading the number aloud it turns out that he was that day’s lucky winner.)

Returning to the question of inspiration, Missy Hyper’s response included the statement, “I wanted to think of words that could describe Carrie Lam” [paraphrase]. She went on to say that she originally just painted the series as a fun prize for her audience members. After giving them away and moving to Taiwan, however, she was surprised at how much she missed having them around the house. Thus, she repainted the series to create the works that we saw at the Taipei exhibition.

Missy Hyper’s other works mirrored “In Da Mood 4 HK” in that they also drew inspiration from experiences of political repression and social control. Dark Side of the Tree Pose combines the legendary Pink Floyd cover with images of the Hong Kong protests of 2019; Traumatized Figures is Missy Hyper’s attempt to turn powerlessness “into an art force to create a new Hong Kong totem;” Be Water Hong Kong—which was sold to the Xinyi bar Yesterday is Not Today, where it now hangs permanently—draws on a Bruce Lee quote that became a slogan for protestors; and Vagina Monologue is Missy Hyper’s reminder to herself that, “in spite of all the twisted noise in the world, righteousness and justice remain within me.”

In short, in Missy Hyper’s works, Hong Kong’s protests give birth to a riot of color and fancy, all of which serve as both record of resistance and commemoration of trauma. But hers was only one of the approaches represented in this exhibit.

Vawongsir: Pop Art Protests

If Missy Hyper’s exploration of the emotion and trauma of Hong Kong’s protests explodes with color and texture, Vawongsir’s art distills resistance to the forced changes in Hong Kong’s system of legal and civil rights down to the flat surfaces, bright colors, and deceptively simple lines of the newspaper comic.

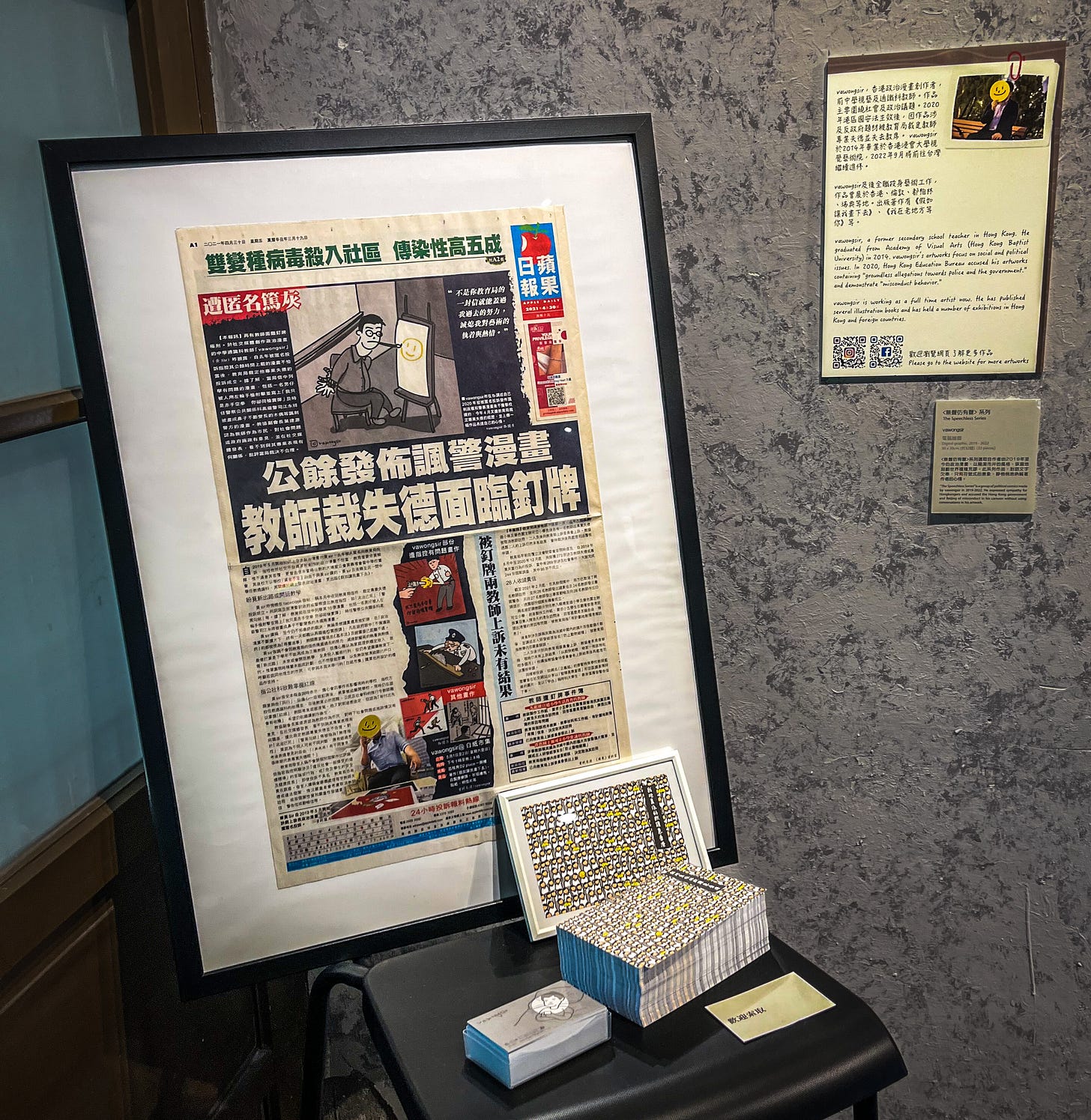

Vawongsir is a recent arrival to Taipei, forced to emigrate due to increasingly intolerable persecution. Formerly a middle school art teacher in Hong Kong, Vawongsir also moonlighted as a cartoonist for Hong Kong newspapers. Among these was the now-defunct pro-democracy newspaper, the Apple Daily 蘋果日報. In 2021, one of Vawongsir’s cartoons showing an artist with his hands bound behind his back and painting a smiley face with a paintbrush held in his mouth was picked up on Chinese media, where it went viral. The result was an avalanche of hateful trolling, abuse and threats. It also resulted in Vawongsir being dismissed from his full-time job as an art teacher, and unable to find new work. Vawongsir ultimately emigrated to Taipei, where he studies and works as a Patreon-supported artist.

In the corner of the exhibition room next to Vawongsir’s works stood a framed copy of Apple Daily’s front page, in which the feature story reported on Vawongsir’s encounter with China’s blacklist. In some ways, this newspaper was as poignant to me as much of the artwork in the room. It’s rare enough in this day and age to see a broadsheet newspaper, but to see one unfurled, framed, and showcased almost like a trophy was particularly striking. At the same time, the contents of the newspaper record the abuse and persecution generated by China’s army of trolls, and provide a real-time snapshot of an individual who is in the process losing a lifetime of community and professional achievement. However trophy-like the staging of the framed newspaper might be, the article’s contents testify to the grim toll exacted in return.

Each of Vawongsir’s panels reveals a scathingly humorous take on Hong Kong’s ever more circumscribed civil and legal rights. Although all bear thinking about, several pieces that stood out to me include: In the top row, a line on a badminton court is bent to favor the defender; a magician standing in front of Hong Kong University’s now-banned Tian’anmen memorial, the Pillar of Shame, performs a vanishing act with the Statue of Liberty; and a line of plain-clothes citizens marching under a red book (a reference to Mao’s “Little Red Book”) emerges on the other side goose-stepping in Chinese military uniforms. In the second row, the orchid petals of Hong Kong’s flag are swept into a dustpan; a person is subjected to a PCR test on their way into the Last Supper; and a security camera is installed over a school blackboard. In the third row, all the squares on the board of a game called “Monopopo” instruct players, “Go to jail;” an apple is buried in the ground in tribute to the Apple Daily; and streams of blood run from doorways marked “education,” “arts and culture,” and “freedom of the press.” In the final row, a person straps on Mao’s Little Red Book in lieu of a face mask; a polar bear balances precariously on the final unsubmerged corner of a book that is sinking into the sea; and in the bottom left corner, the words “50 years” spill off a conveyer belt into a trash bin (a reference to China’s promise to maintain Hong Kong’s system of governance unchanged for the first 50 years after retrocession to the PRC).

Many of these cartoons are truly laugh-out-loud witty. But there is also something grim about them, particularly in the gallows humor that this collection of single-frame comics presents in aggregate. Though they may elicit some laughs, these pieces hardly offer up a thigh-thumpingly good time. Instead, they point us towards the clear-eyed grasp of political realities amongst some of Hong Kong’s staunchest pro-democracy activists.

Fly: Raging with the Machine

The works of the final exhibitor, Fly—who seems to have shut down social media—operate in a very different medium than the previous two artists. Here, instead of a physical art object, the work consists of screen shots of the artist manipulating Google’s predictive algorithm for Cantonese text entry. And although the resulting poems were displayed on plaques alongside the artist’s explanations of the work, the main focus of the exhibition was a video screen which showed the process of writing.

Perhaps the most striking of these works was the poem china is motha fuckin. The script that emerges from Fly’s process is esoteric at best, with the artist noting that the poem “seems to be religious.” Even to my non-literary, non-native-speaker eyes, it is evocative: “This is the wood-cut Buddhist scripture/We must give blessing/Glass divination is the light of him/Smashes consciousness/The breath of wood fells its forest town … ”

Fly’s process, however, makes use of altogether less pious language. To understand this, a brief word about typing in Chinese: In most Sinophone text-entry systems (with the notable exception of Taiwan), some form of Romanized script is used for a phonetic input, from which an algorithm identifies the most probable string of characters, usually listed in descending order of likelihood. (In the video below, you can see how this process works.) These algorithms can also be trained. For example, my Chinese name is a somewhat uncommon string of characters, but after typing it a couple of times, my computer recognizes my name as the most likely combination of characters for me. If I transfer to a different computer, however, I will still have to hunt for my name. In short, modern computing enables a ranked lexicon that balances general linguistic principles and personal habits of use.

In Fly’s poetry, however, the artist does not use Romanized Cantonese inputs. Rather, English profanities directed against the Chinese and Hong Kongese governments are typed into the box, and the artist simply accepts the top-ranked string of characters produced by Google’s algorithm. Because Google’s algorithm thinks that Fly is typing in Cantonese, the algorithm searches for the nearest likely string of characters in Cantonese. Thus, the invective “chinaismothafuckin” produces the rather pious-sounding “This is the wood-cut Buddhist scripture.” Elsewhere, Google converts profanities leveled at Hong Kong’s former Chief Executive Carrie Lam, the police force, and the legal system into similarly devout-sounding Cantonese text.

A key feature of this work is that, without Fly’s video, there is no way to reverse-engineer the artist’s inputs, as the outputted characters could be the result of an almost infinite combination of letters. By filtering the artist’s enraged language through the trainable algorithm of Google’s Sinophone text entry system, the poem becomes an almost unbreakable cipher. In the face of intensive state surveillance of artists’ works, speech, and actions, approaches like Fly’s show how artists working across a variety of media can still leverage their creativity to find ways to circumvent ever more draconian state policies of surveillance, suppression, and control.

Raging Against the Machine

The room in which this exhibition took place was full of color, humor, beauty, and wit. The opening of the show also served as a space where members of Hong Kong’s diasporic community in Taiwan could celebrate and reconnect.

There are many things worth thinking about in connection with this show, and it would take much more time and space to do justice to the layers of meaning that we could unpack from these works. On a fundamental (and very local) level, however, this exhibition points to the kinds of everyday freedoms that Taiwan stands to lose should it ever be forcibly reunited with China: art that in Hong Kong ignited government backlash intense enough to force artists from their homes is, here in Taiwan, simply an uncontroversial showcase of local artists’ works, suitable for an afternoon at a stylish café on the outskirts of town.

In evaluating this exhibit, though, it’s important to avoid sliding into an easy narrative of artistic triumph in the face of adversity. Beneath the riotously colorful surface of Missy Hyper’s acrylics, or the sleek 2D planes of Vawongsir’s cartoons, or the blinking cursor of Fly’s poetry, there is also a profound sense of grief, and an abiding anger over a lifeway that has been forcibly—and probably irrevocably—taken away. At no point did the citizens of Hong Kong have any say in this. They did not choose colonization by the British. They did not have any real say in the process of retrocession. Ultimately, even the relatively modest promises made to Hong Kongese citizens before the handover have proven to be worth less than the electricity it takes to load the PDF of the Sino-British Joint Declaration.

As I said at the very beginning of this post, I am not an expert in Hong Kongese history or culture. But it seems to me that Hong Kong’s current trials resonate with the issues facing many other areas of the world. Hong Kong is a living example of the ongoing disenfranchisement that is one of the most salient legacies of colonialism. It is a laboratory for the most pernicious effects of unregulated surveillance arising from state entanglements with big data.

For readers in America, where free speech is an assumed right, the idea that any of the artworks featured above could create legal problems for artists, let alone force them to emigrate, would be met with incredulity. And yet, for the roughly 40% of America’s population that seems incomprehensibly hell-bent on arguing that a racist, misogynist, ableist, homophobic, corrupt, criminally negligent, irredeemably venal, insurrectionist beneficiary of the Electoral College might still have personal and political charms, Hong Kong offers a cautionary tale of the dangers of a legal system that can be twisted to serve the caprices of the ruling class.

The American Constitution may be a flawed document created by flawed men, but it still guarantees certain rights and freedoms, and lays out the mechanisms by which those rights and freedoms are to be upheld. In the past few days, however, suggestions that the Constitution can and should under certain circumstances be “terminated” have been met on one side of America’s stereophonic political landscape with a resounding chorus of he-didn’t-mean-its. In these laugh-inducingly depressing circumstances, Americans would do well to meditate on the case of Hong Kong, where the defense of civil rights has fallen to students, artists, and activists who are willing to risk their careers, communities, livelihoods, and futures in order to resist a state that is intent on chipping away at civil liberties with all the loving patience of Godzilla armed with Thor’s hammer.

And when we’re done thinking about that, we would do well to do what we can to support those artists, activists, and citizens who continue to fight for their right to be heard.

An earlier version of this post described Missy Hyper’s performances as an online talk show. This has been corrected to reflect the fact that the show was a live show, and recordings were later posted online.