Happy Pride Month, everyone!

I’d like to start with a disclaimer: I am not a RuPaul’s Drag Race afficionado. The interpersonal drama that provides the lifeblood of reality TV stresses me out—I belong more to the Ms. Marple demographic (Joan Hickson or bust). In general, I rely on friends for updates, analysis, and links to the show’s important highlights. So if you’re looking for incisive commentary on how the mega-hit reality show’s reigning champion, Nymphia Wind 妮妃雅 瘋, stacks up against her predecessors, this missive cannot help but disappoint.

But Nymphia Wind’s victory offers plenty to discuss from an outsider’s perspective as well. For starters, even as a lay person, it was immediately clear to me that Nymphia’s ascendency on drag’s most public stage was an important moment for Asian representation in mainstream American media.

The main reason that Nymphia Wind’s victory has repeatedly demanded my attention, however, is not for its importance within the Western mediascape, but for the way that it so aptly illustrates the different trajectories of Taiwanese and Chinese society over the past couple of decades. Most importantly, the freedom to practice drag openly, and without coming under official scrutiny or censure, is a gift that is almost taken for granted in Taiwan, but which looks increasingly precarious in China in recent years. In short, Nymphia Wind illustrates how, despite all the political challenges Taiwan faces, “Die Luft der Freiheit weht (immer noch)” in this small island nation.1

So if you’re interested in why we should take seriously both Nymphia Wind and the social and political phenomena she represents, please read on!

Taiwan, Drag, Nation

In the words of Vox contributor Daniel Villareal, “Drag has always been political,” and this season’s finale on RuPaul was no exception. Though it would be a stretch to say that Nymphia Wind’s victory speech offered audiences a treatise on Taiwanese identity, the drag star still dedicated her win to the nation that she called home for much of her upbringing: “To those who feel like they don’t belong, just remember to live fearlessly and have courage to live your truth, and Taiwan this is for you!” (NB, because Elon Musk and Substack are fighting, I can’t embed the clip of Nymphia’s victory speech here.)

In Taipei, where Nymphia honed her skills, audiences at live watch parties erupted when she was announced as the winner. Emotions ranged from pride at Asian representation and excitement of local LGBTQ+ audiences, to joy at an opportunity to train a positive spotlight on Taiwan and happiness at witnessing a hometown performer make good on the global stage.

Not to sound blasé, but these reactions were to be expected. Taiwan’s LGBTQ+ community as a whole may enjoy significant legal and public support, but individuals who choose to come out often suffer from strained family relationships—just as in America, it’s easier to support the queer community in the abstract than when it disrupts cherished assumptions of what one’s nuclear family will look like in the future. Thus, opportunities to gain visibility remain valuable, even in a society as open as Taiwan.

Nymphia Wind’s win also speaks to concerns that stretch beyond Taiwan’s queer community. Many Taiwanese who are proud of the country’s musical, culinary, and cinematic achievements recognize that international coverage of Taiwan is often reduced to the current performance of chip giant TSMC and the number of Chinese planes (or, more recently, submarines) encroaching on Taiwanese airspace on any given day.

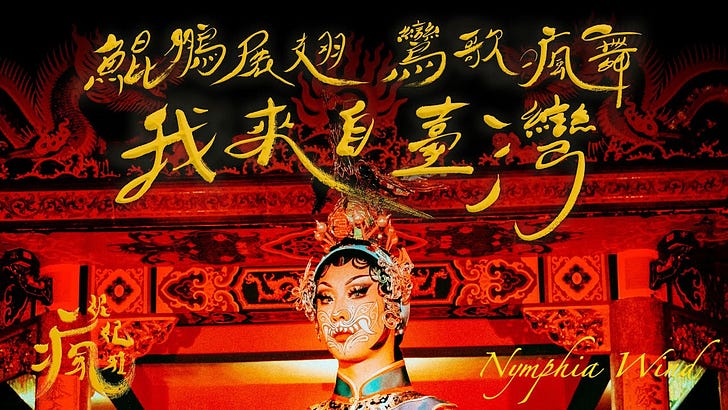

In contrast, Nymphia’s performance combined the drag staples of impressive athleticism, skilled craftsmanship, acerbic wit, camp, and raunch with visual markers of Taiwaneseness, offering a window on a very different kind of Taiwan. Were you unaware that Taiwan claims bubble tea as a home-grown invention? Well, after one of Nymphia’s most striking costume reveals, RuPaul fans know (see the photo at the top of this post)! And lest anyone miss that these are Taiwan references, Nymphia issues plenty of content that hammers home the centrality of Taiwan to her stage identity.

What strikes me as most important about the reaction to this win, however, is that it was not limited to LGBTQ+ circles. Immediately after Nymphia’s win, Taiwanese media outlets began to report on the victory. Even outgoing President Tsai Ing-wen issued a statement:

Now, first of all, I’ll confess that I’m tickled by the collision of drag culture and officialese in this Tweet. More importantly, there is in Tsai’s post a subtle slippage between the “fearless” living advocated by Nymphia and the open acknowledgment of Taiwaneseness. Tsai’s Tweet seems to suggest that open acknowledgment of one’s Taiwaneseness on a global stage is its own form of fearless living.

At the time Tsai (or her media team) posted this, I assumed that would be the end of it. After all, even a somewhat cursory acknowledgment by a sitting president is no small thing. But Tsai’s administration went farther, leading to the next major visual moment that demanded my attention: the vision of a drag superstar, decked out in psychedelic yellow (and flanked by a handful of local queens) performing in the Presidential Office Building. The very first clip I saw opened with an image of Nymphia Wind dancing in front of a bust of none other than Sun Yat-sen 孫中山, the founder of the KMT.

Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925) was an anti-Qing activist and founder of the Kuomintang 國民黨, the party that (basically) ruled China after the fall of the Qing dynasty. It is also the party that maintained single-party rule and martial law in Taiwan from 1949 until 1987. Today, Sun is revered in both China and Taiwan as among the nation’s foundational figures.

In hindsight, it’s easy to gloss Sun Yat-sen as the forefather of Taiwanese democracy. But this take ignores the fact that the Kuomintang (KMT) was deeply conservative and paternalistic, and that “democracy” was to be achieved only after a period of preparation, led by the great and the good (most of whom naturally belonged to the party). Public morality was counted among the KMT’s top concerns, and it is difficult to imagine how performances like Nymphia’s—provocative, raunchy, and unmistakably queer—could have made it past censors in KMT-era Taiwan or Republican-era China. Equally implausible is the idea that earlier, more socially conservative presidents would have invited a drag performer into the Presidential Office Building and enjoyed the show in the way Tsai Ing-wen appears to have:

So here we have an openly queer performer, launched to global fame on the back of an American reality show, feted at the Presidential Office Building, whose performance is juxtaposed with an image that recalls the conservative social roots of modern Taiwanese society. It would be easy to simply take this as a moment to sit back and give thanks for the undeniable achievements of the gay rights movement in Taiwan.

But Nymphia’s win is not simply a moment to appreciate the progress of LGBTQ+ rights in Taiwan. It is also a moment that we can reflect upon how tenuous some of these gains can be. Here, China—that other nation that regards Sun Yat-sen as a key historical figure, and which is determined to bring Taiwan under Beijing’s direct rule by any means necessary—is a case in point.

Meanwhile, in China

In Taiwan, a drag queen can perform for the president. In China, the government has gradually stepped up its campaign to solve a national “masculinity crisis” by cracking down on “sissy men” in media.

In some ways, high-profile opprobrium of liberal forms of gender expression is nothing new in China. A decade ago, Wu Jing 吴京, a martial arts star-cum-film director and star of some of China’s most jingoist films, including Wolf Warrior 2 战狼 2, went on record about his take on the question of Chinese masculinity. The actor stated that, were his son were to be a “sissy” 炮娘, he would resolve the situation by giving the boy a “big slap” 大嘴巴抽他.

In recent years, China’s “demographic time bomb” has spurred the government to involve itself more directly in this campaign. In the hopes of boosting declining birth rates, the government has banned effeminate men on TV, shut down social media accounts of influencers who depart from “traditional” forms of gender expression, attempted to reinvigorate the manly spirit of school-aged boys with more physical education classes, and even imposed an unofficial ban on K-pop groups touring China.2

The CCP’s war against diverse gender expression mirrors a broader shift in official discourse around gender roles: for the first time in decades, China’s Politburo finds itself without a single female member, and women are increasingly receiving the message from the government that their most important contribution to the nation is reproductive. Apparently, in 21st-century Chinese political practice, women can hand their half of the sky back to the men.

Defining Democracy

Talking about China brings me back to the bust of Sun Yat-sen in front of which Nymphia performed. China, of course, lays claim to Taiwan, regarding the island nation as a breakaway province. In Taiwan, which rejects Beijing’s rule, the most prominent issue in the last presidential election—and in most every election—was “the China issue.”3

There are good reasons that domestic political discussions return so often to the subject of Taiwan’s neighbor across the Strait. As just one recent example, on May 20th, William Lai 賴清德 of the Democratic People’s Party (DPP) was inaugurated as Taiwan’s new president. In response, China launched a series of “punishment” military drills in the waters around Taiwan, reminding Taiwanese citizens of the Xi Jinping government’s increasing willingness to promise enforcement of joyful national unification at gunpoint.

Coinciding precisely with, though largely unrelated to China’s military drills, Taiwan also experienced its largest political protests in a decade. Dubbed the Bluebird Movement, multiple days of protest attracted between 70,000 and 100,000 participants who gathered to voice opposition to a series of of “reform” bills rammed through the legislature in contravention of procedural norms. This situation also proceeds directly from Taiwan’s most recent election results: although William Lai won the presidency, the DPP lost their majority in the legislature, and the opposition Kuomintang (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) collectively hold enough seats to pass the bill.

The Bluebird Movement took place against a complex political background that draws together concerns for Taiwan’s sovereignty, Chinese influence on domestic politics, and the nature of political participation. The KMT and TPP argue that these bills will strengthen Taiwanese democracy by increasing oversight of the presidency. In response, hundreds of lawyers and academics, as well as organizations like the Taiwan Bar Association, have voiced serious concerns about the potential for abuse contained within these particular bills. The bills have also drawn criticism for eroding governmental separation of powers. Despite the spontaneous outpouring of public opposition and widespread academic and professional condemnation, however, the KMT and TPP pushed the bill through (followed by an immediate announcement that they intend to use their expanded powers to establish what amounts to a muckraking committee to hunt for corruption in the DPP). Just as is so often the case in contemporary American politics, the meaning of “democracy” espoused on either side of the aisle varies drastically.

For those of you lured into this post by promises of drag queens, I’m not going to go into any more details here. If you’re interested in a more in-depth discussion of what’s at stake, however, I strongly recommend reading the fabulous post by the legal-scholar and historian super-duo of Michelle Kuo and Albert Wu (which includes a round-up of English-language writing on the topic across a variety of platforms).

From the Exceptional to Everyday Freedoms

It would seem that I have somehow veered off course. How did we get from a banana-obsessed drag queen to China’s “punishment” military drills and Taiwanese legislative arcana?

I’ll be honest, it’s a stretch, even for me. But when Western media talks about tensions between China and Taiwan, there is a tendency to focus on the Big Issues: democracy, militarism, sovereignty, freedom, self-determination. (There’s a similar tendency in coverage of other flashpoints like Hong Kong.)

In contrast, the euphoria that Nymphia’s win sparked in Taiwan, and the embrace of the social diversity inherent to drag provides a concrete point of contrast with the current trajectory of China’s social environment. Despite contentious debates about the nature of democracy, post-martial-law Taiwan has generally trod the road toward openness and freedom of choice. In the early 21st century, China made similar, albeit more modest inroads in LGBTQ+ rights, notably in delisting homosexuality as a psychiatric disorder. This progress, however, is now being reversed. For example, in addition the government’s anti-sissy campaign, a Chinese court ruled in 2020 that a textbook describing homosexuality as a mental disorder “did not ‘contain factual errors.’”

As the winner of a globally televised competition, Nymphia Wind is by definition an exceptional figure. As such, I want to avoid placing too much weight on one outlier as a means of justifying an argument in favor of a particular group, performance medium, or aesthetic. But exceptional figures like Nymphia Wind provide a valuable opportunity to think through issues that affect broader communities. In this instance, the celebration of drag centering on Nymphia Wind helps move us away from heady, abstracted discussions of historical legitimacy or the nature of democratic representation, and towards concrete considerations of the banal, everyday stakes in the ongoing contest over Taiwanese sovereignty. Whether you’re a long-standing fan of drag, an occasional audience member, or completely unaware of this (sub)cultural phenomenon, the individual freedom to pursue the life and craft the image that one desires for oneself constitutes a basic human right, no matter what demographic anxieties a government may be facing.

So by all means, let’s celebrate Nymphia Wind’s victory as an important milestone for Asian representation in an American mediascape and queer community that often devalues Asian contributions and talents. Let’s enjoy the creativity of the costumes, the post-production tell-alls, and the analyses of how the first Taiwanese winner of RuPaul stacks up against other season 16 competitors and previous winners. But as we do so, let’s spare a thought for all the reasons that Nymphia’s brief, spontaneous tribute to Taiwan remains so critically important.

“Die Luft der Freiheit weht” (“The wind of freedom blows”) is the motto of Stanford University. While these kinds of official mottos are usually rather arcane knowledge, Angela Merkel related how this phrase coalesced her hopes for democratic reform as the Wall came down in Germany. While there was no wall to pull down in Taiwan, the right for democratic representation was equally hard-fought here. It is for this reason that I choose to play on Nymphia Wind’s name for the title of this post.

Some of these restrictions have loosened in the past year or so. Nevertheless, the point stands that China’s government is deeply invested in traditional gender roles, and blames its current demographic partly on the alleged feminization of the nation’s young men.

This is a slight over-simplification, but Prof. Adrian Chiu of the University of Tübingen provides a good primer on the relative paucity of policy debates in Taiwanese elections.