Well, I’m back in Taipei. It was a beautiful, chaotic, whirlwind, jet lagged trip home [Michigan] for the holidays (complete with a white Christmas and sightings of wild turkeys right outside our window!) It’s also great to be home [Taipei] for a beautiful, chaotic, whirlwind, jet lagged relaunch into my next few months in Taiwan.

I will confess, I don’t have a plan for this week’s blog post. Indeed, my time in the US was blissfully devoid of any advance planning. As such, the first installment of 2023 might be even more meandery than usual.

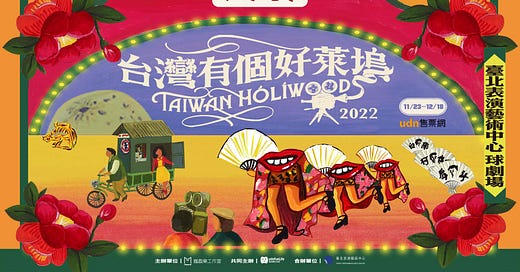

That said, if you want to hear about a bilingual Taiwanese musical called Taiwan Hollywood 台灣有個好萊塢, and all the opportunities it presents for jazz hands, please read on! (Alternately, if you just want to listen to some fun songs, scroll down to the penultimate section of this post for lots of Spotify and YouTube links!)

Taiwan as Research

Before beginning, does anyone here remember Taiwanese National Day? Does anyone remember the charming youth who demanded, “Where’s [President] Tsai Ing-wen?” Does anyone remember the private performance for said president in which jazz hands featured prominently?

I do.

At the time, I suggested that the film canon laid out in Taiwan’s National Day celebrations constructs a Taiwan that is worthy of international recognition as a distinct social, political, and cultural entity in its own right. Likewise, the performance of Taiwan Hollywood for the great and the good of Taiwan’s political class established Taiwan’s film industry as having its own kind of cultural capital, worthy of being mentioned in the same breath with epicenters of global cultural production such as Hollywood. At the same time, I am aware that there were lingering questions left unanswered in my original take on Taiwan’s National Day celebrations.

Because I know these questions have doubtless been eating at you since last October, let me now reassure you, dear reader: it turns out that there is greater context to this musical than just a random, one-off performance streamed on YouTube. The performance for Tsai Ing-wen was actually the introductory/concluding scene to the 2019 musical Taiwan Hollywood 台灣有個好萊塢, a bilingual Mandarin-Taiyu musical about the Taiwanese film industry. (NB: Taiyu is the Mandarin term for the Taiwanese language, a Sinophone language that was once the predominant form of vernacular Chinese in Taiwan. Because I’m going to be thinking through issues of Taiwanese identity, I’m going to use the term Taiyu when referring to the language so as to avoid ambiguity.)

By National Day, the show was in rehearsals for a December 2022 revival at the newly-opened, state-of-the-art Taipei Performing Arts Center. The company responsible for the production is the Taipei-based Studio M 瘋戲樂工作室, an organization that bills itself as “a musical theater troupe that is not just a theater troupe” 一個不只是劇團的音樂劇劇團. According to their company bio, “To Studio M, creating theater is not just about creating theater. Rather, it’s about putting beliefs into action, stimulating the industry, giving audiences a conception of musical theater, and exploring even more thematic and formal possibilities for Chinese-language musical theater” 對瘋戲樂工作室來說,做戲不只是做戲,而是在實踐理念、刺激產業、帶給觀眾更多對音樂劇的想像、挖掘中文音樂劇在題材與形式上的更多可能.

None of this answers how this musical came to be featured in a private performance for high-ranking government officials (although I will continue sleuthing). But when we consider the experimental impulse underlying Studio M’s work, as well as their mission to create a corpus of Chinese-language musical theater, there was perhaps a natural affinity between this musical and the theme of last year’s National Day laser light projection show. All that leaves, then, is the question, if “creating theater is … about putting beliefs into action,” what beliefs do we find in Taiwan Hollywood?

Taiwan as Hollywood

In terms of plot, Taiwan Hollywood is as classic a Broadway romcom as they come: Frustrated but talented boy playwright has meet-cute with innocent girl aspiring to movie stardom. Mutually inspired by one another, they team up with an intrepid (albeit scrappy) group of creatives to shoot a Taiyu film. Boy and girl have misunderstanding (resulting in a brush with prison and sex work, respectively), but it all blows over by the end of Act II, the group makes their film, boy and girl marry, and everyone wins a Golden Horse Award (sort of like the Oscars of the Sinophone world.)

Despite the significant similarities, there are also several areas where Taiwan Hollywood departs from the Broadway musical. One of those ways is in the music, which we’ll get to in just a little bit.

Language is another critical way in which this show departs strikingly from pretty much any Anglophone musical theater pedigree chart in the Cole Porter-Rogers and Hammerstein-Stephen Sondheim-Andrew Lloyd Weber-Jason Robert Brown tradition. More specifically, unlike any mainstream Anglophone musical I can think of, this is a resolutely bilingual musical.

Bilingualism is introduced as a problematic of the play from the our very first meeting with the play’s female lead, Qiuyue 秋月. In this scene, the naïve movie fan Qiuyue repeatedly tries to quote Taiyu films to the male lead, Zhenghua 正華. In a classic case of mistaken identities, Zhenghua is, unbeknownst to Qiuyue, the screenwriter of said films. His initial pleasure at encountering a fan quickly fades, however, in the face of Qiuyue’s mangled Taiyu pronunciations. Indeed, one of the gags in this scene is his increasingly despairing attempts to correct her pronunciation—a gag that, on my second viewing of the play, turned into an echo of what was happening around me in the audience, where elderly viewers sitting near me scoffingly corrected the mispronounced Taiyu from their seats in audience in advance of the character on stage. (This gag was translated into a recording session for a promotional video that you can watch on the company’s Facebook page.)

In contrast to the linguistic melding of Taiwan Hollywood, American musicals are largely monolingual. And no, repeated exclamations of “La vie bohème,” villagers who inexplicably shriek “Bonjour” out their windows first thing in the morning, or a gaggle of children who manage to rhyme the words “adieu” and “you,” despite their ecclesiastically competent live-in governess, do not count as counter-evidence.

Throughout the play, Taiyu is a source of both identity and dramatic tension. For example, a major source of conflict early in the musical is the fact that Qiuyue lands a leading role in a Taiyu movie, despite speaking barely a lick of Taiyu. Thus, Qiuyue’s character arc is partly a story of gaining legitimacy through mastery of Taiyu. Conversely, two of the Taiyu film stars in the musical’s first act abandon Taiyu in the second act in favor of standard Mandarin, a move that is handsomely remunerated—a story of gaining economic security but compromising legitimacy through the abandonment of Taiyu.

Finally, when the male lead is released from prison in the second act of the musical, he tries to gather his old cast of characters around himself to revive his creative career. In response, his old colleagues one by one tell him that Taiyu films are dead, and Mandarin is the future. Eventually, he wins over his former collaborators with the promise that they will produce a “Mando-Tai film” 国台语片—a story of gaining legitimacy through reclamation of Taiyu in the context of a polyglot society.

This final stage of the musical, in which the characters’ “Mando-Tai film” wins a slew of Golden Horse awards, is where Taiwan Hollywood’s vision of a multilingual Taiwanese identity becomes most obvious. Where Qiuyue initially gains legitimacy through mastery of the local language, and where other characters lose legitimacy through their abandonment of Taiyu, the end game for this musical is a linguistic ecosystem in which Mandarin and Taiyu are both necessary languages, and in which which the lack of either impoverishes both comprehension and cultural competence.

This vision of necessary bilingualism was borne out in the musical itself. In a nod to declining rates of Taiyu proficiency in Taiwan’s younger generations, all of the Taiyu songs and dialogue were supertitled. Because language was not an intrinsic barrier to comprehension, many of the Taiyu gags received big laughs from the audience. But there was also a subset of jokes that drew titters from a consistently smaller portion of audience members in both of the performances I attended. Although I have no way to prove this, my strong suspicion is that these were jokes that relied on Taiyu wordplay or other colloquialisms that simply didn’t translate into the supertitles projected on the side of the stage. At these moments, the significantly smaller subset of truly bilingual audience members were the ones who were in on the joke. (With apologies for the poor quality of the cell phone recording below—which was permitted at this moment in the hall—the projected supertitles can be seen dimly on either side of the stage, along with some of the animation capabilities of the proscenium arch projections during the cast’s curtain call reprise on Friday, 16 Dec. 2022.)

Now, I’ve just spilled a lot of pixels on discussing plot and language, areas in which I have no official training or expertise. What’s interesting to me, though, is the way this vision of polyglot Taiwan comes to be reflected in the show’s musical score.

Taiwan as Broadway

What does a “Chinese-language musical” sound like?

Well, in some ways, it sounds a lot like a musical you might hear on Broadway, or in London’s West End. Like many musicals, a small pit band is used to create a variety of musical colors and sound effects, and the score makes ample use of recurring themes that transform throughout the musical based on dramatic situation and character development.

The music itself is an eclectic mix of styles that are used to emplace listeners in the 1960s musical milieu in which the narrative unfolds. For example, the opening number (the very scene that Tsai Ing-wen saw for National Day celebrations) starts with a reference to the kind of military songs that would have been a staple of public life during the KMT era. At roughly 1:10, however, the soundscape transitions to an electric guitar/saxophone/drum set accompaniment that calls to mind mid-century rock of the kind that would have been emanating from American military bases at the time. (NB: The following Spotify links are all to the official cast recording of the musical. Here on Substack, you’ll only be able to hear previews that do not line up well with the sections of the songs I’m discussing here, so please click through to Spotify to hear the full tracks and to support this theater company’s work.)

Elsewhere, the score captures the mid-century global appetite for Latin music through the use of dance rhythms like the cha-cha. Latin rhythms had been popular in the Sinosphere since the first efflorescence of popular song in 1920s and 30s Shanghai, as with this rhumba performed by Bai Hong 白虹, and continuing through Grace Chang’s 葛蘭 star turn in Mambo Girl.

An example of these Latin dance rhythms is the song “Home, home, home” 家 家 家, in which the female lead has just shared her pride in the fact that she hasn’t been home for several days as she pursues her theatrical dreams. In response, several of musical’s theatrical veterans describe the months and years since they’ve been home. In this performance, the Mandarin word for home, jia 家, is repurposed as a near-homophone for cha-cha, and becomes the rhythmic basis for a song that humorously addresses the sacrifices made by performers in pursuit of their artistic careers.

The final recurring soundscape that appears in this musical is what I think of the as the “true love” soundscape, which largely aligns with major trends in contemporary musical theater power ballads. Piano chords that move frequently between major and minor modes to strike a bittersweet emotional tone, combined with simple guitar, wistful flute, or sentimental cello accompaniment provide a platform for characters to express their feelings clearly, while tugging on the heartstrings of audience members. At the same time, the harmonic structure of songs like this one are scalable, leading to full-cast “happily ever after” performances (e.g., the buildup starting at c. 2:45).

Taiwan as Taiwan

Although many of the musical resources deployed throughout this musical are ones that you could find in any Broadway musical, and although this show takes the cultural capital produced by Hollywood as an aspirational metric of success, there is something about the aesthetic of this musical in performance that strikes me as a product of the distinct cultural forces that are unique to Taiwan.

Part of this is of course linguistic. The play’s unique combination of Mandarin and Taiyu contributes to a vocal sonority that English simply can’t produce. This shouldn’t be surprising—in genres like art song and opera, French, German, and Italian linguistic sonorities operate in concert with musical factors to create the distinct character of those vocal repertories.

But another major part of what makes this musical stand out is the vocal aesthetic that characterizes a lot of the singing. On the one hand, the vocal aesthetic of this show is certainly miles from the studied wispiness of Taiwanese megastars like Hebe Tien 田馥甄.

On the other hand, the belting that fills this show is equally far removed from anything that might be produced by artists as varied as Ethel Merman, Idina Menzel, Bernadette Peters, or Audra McDonald. Perhaps the closest analogy that springs readily to mind is a Kristin Chenoweth-style twang belt, but even that is not quite what’s happening with many of the female singers in this this cast. Instead, the belt employed by the vast majority of this cast lies somewhere between the robustness of Broadway stylings and the exaggeratedly sylphlike femininity that characterizes much (though not all) of contemporary Mandopop. (This trend is not as pronounced in the original cast recording I have linked to here, but the general principle still holds with voices such as that of Qiuyue.)

As I said above, the plot of this musical seems to put forth a vision of Taiwan as a multilingual society in which the peaceful coexistence of Taiyu and Mandarin is a mutually enriching arrangement. Though the musical score overlaps with this vision, the two are not completely redundant. In the score, a global set of influences is unified under the rubric of a distinctly Taiwanese performance aesthetic. As with the text to the play, though, the implication is that, far from representing some sort of cultural monolith, Taiwanese society’s most defining characteristic is its linguistic, social, and cultural diversity.

I haven’t really had time to organize my thoughts here in a way that would lead to a pithy conclusion—or any conclusion, for that matter. But I’m interested in this musical because of the way it clearly aims to insert itself directly into discussions of contemporary Taiwanese identity, based on a highly selective version of Taiwanese history. Thus, in lieu of coming up with a conclusion of my own, I leave you with a final word from Taiwan Hollywood’s composer and music director, Wang Hsi-wen 王希文, on his hopes for this musical: “Regardless of whether it’s Taiyu or Mandarin, I hope that this fun and moving story will allow you to hear the beauty of our language, and rediscover the glory we once had” 不論是臺語還是國語,希望透過這個促咪動人的故事,能讓你聽見屬於我們語言的美麗、找回我們曾經擁有的光彩.